|

|

ZHU WEI: LIVING IN HISTORY

Jeffrey Handover

As I began writing, the newspapers heralded 1000 days until the return of Hong Kong to China. The stark significance of this round number is more easily grasped and the descending numbers that follow it more real than the endless stories of airport negotiations or the continual meetings of the Joint Liaison Group. We now live self-consciously in the midst of history. It seems fitting as we tick off the days that Zhu Wei’s paintings are gobbled up by collectors faster than Sunday dim sum. Zhu Wei is the artist of the countdown. Embedded in our now shared history, Zhu Wei comments from across the border on the motherland preparing to embrace us: the family stands peering out the doorway (“the Sweet Life No.4), a child points, 1997 is on its way.

Discovered at Guangzhou’s China Art Expo in November, Zhu Wei was the undisputed star of last spring’s New Trend exhibition in Hong Kong. Certainly, the interest in Chinese Political Pop art generated by the success of the exhibition China’s New Art, Post-89, an the lure of the undiscovered and the unhyped are all contributing explanations, but other factors found in the arty itself may better explain Zhu Wei’s broad and meteoric rise in popularity. His work has struck a cultural chord in end-of-an-era Hong Kong, where unease and optimism, some willed, some truly felt, tug at the city’s heart.

Even those who do not read their surface text of Chinese characters and historical references realize these paintings are “radiant with consciousness” (nothing in his paintings seems accidental or purely decorative), that even if there were no market for his work, Zhu Wei would be impelled to paint them. He is a storyteller, a chronicler of Beijing. Paradoxically, we listen to him because he seems more interested in telling the story for himself than for us. We buy because he’s not selling.

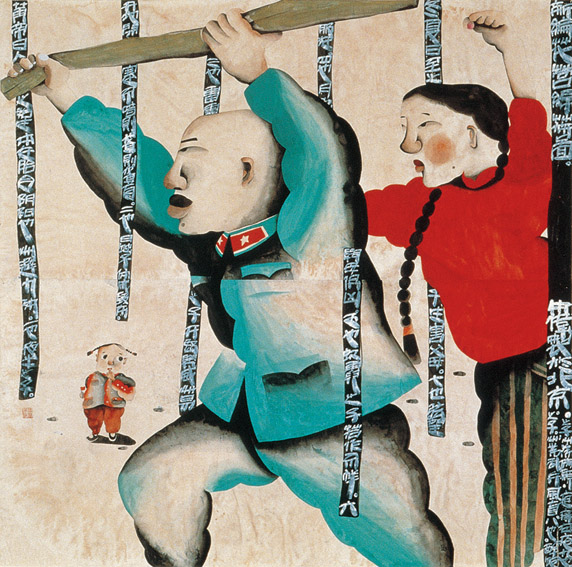

The stories he paints are bittersweet tales to Hong Kong eyes. We laugh at the Punch and Judy buffoonery of the bloated cartoon characters while keeping our hands on our passports and out one-way tickets. Hong Kong compatriots-to-be want to believe that the larger than life People’s Liberation Army officers living “The Sweet Life”, are, despite their size, as insubstantial as they seem, like puppets of chicken wire and cloth. There is something almost Chaplinesque about them and their bald, goonish subordinates with big lips like a child’s valentine, looking as if the Little Tramp had stumbled into a closet of clothes fine size too big. We want them to be Chapin the Tramp not the Great Dictator.

|

|

|

Zhu Wei is part of a broad creative movement cutting across art, literature, and film that is expanding the realm of private expression and challenging the cultural hegemony of the Party with criticism and indifference. Like his Post-89 cohorts, Zhu Wei is irreverent and cheeky, but there is a sweetness, a gentleness to his brush missing from the more dominant cynicism of Political Pop with its pox-on-both-your-houses attitude towards Marxist and materialist alike. Zhu Wei is the Garrison Keillor of Chinese Painting, a gentle deflator of pretension, a chronicler of the everyday who sidles up to the humour in daily life rather than hitting it head-on. Even his most recent erotic works are more suggestive than explicit. He doesn’t go for the belly laugh but the knowing smile.

|

There is some of his paintings, a wide-eyed girl with braids who observes the adults scurrying around her (for example, “New Positions of the Brocade Battle No.1). Her very innocent presence reveals the Emperor’s nakedness, the posturing, the pretension of youths with their Walkman on the way to McDonald’s, the delivery service which is more promise than delivery, the officers sipping Cokes and living the good life.

Part and parcel of Zhu Wei’s gentle humour and his popular appeal is the inclusiveness of his art. There are no enemies, no us-them divide, no malevolent Other to blame, just a community of imperfect souls with their shared human foibles and follies. Zhu Wei is a satirist without venom, a moralist without brimstone. He is gently pushing outward the envelope of private expression and cultural criticism, casting his critical net far and wide to capture cadre and consumer alike. His work may not be the “poisonous weeks” Party hardliners denounce, but they are weeds cracking the cement of authoritarianism.

After ten years in PLA, he paints himself and his erstwhile comrades in their ill-fitting bagginess with the befuddlement they seem to deserve. They are not the architects of the new order but its pliable agents, swept along by currents and commands beyond their control and comprehension.

Soldier and civilian alike view the new world with impassive wariness. Look closely at the paintings: in almost none of them do figures look directly at each other or at us: they are always glancing up (”Descended from the Red Flag No.2”), sideways (“The Story of Beijing No.8”), or out of the corners of their eyes (“The Story of Beijing No.21”). If anyone looks straight ahead, it is the children with their wide-eyed innocence and wonder, na?ve to how the world works. The real action takes place outside the frame, beyond the stage of their lives and Zhu Wei’s actors know it. The script for their lives is written by unseen others.

We catch ourselves in mid-smile, as an aura of unease seeps through the humour. Zhu Wei’s wary characters seem to be listening for distant rumblings, trying to gauge the changing wind. However foolishly they may be portrayed, they are not fools: get rich quick, drink that Coke fast, open that foreign bank account and hope for the best. They, better than Western investors and analysts with their faith in progress’ straight line, seem to know that the winds of politics can suddenly shift. Every innocent act today can become evidence for the prosecution tomorrow.

Zhu Wei captures the intrusion of the new world of Chinese market socialism into old Beijing with a muted palette of browns and greens that gives his work the look of faded wall posters, of cave paintings from a distant time. The medium is in part the message: with a tinge of nostalgia he records this new world as plain fact neither to be celebrated nor overtly condemned. Zhu Wei greets the new China with a shrug, a soft smile and a sideways glance down the avenue.

998 and counting.

6 October, 1994

First published in Zhu Wei - The Story of Beijing, p.16-19, published by Plum Blossoms (International) Ltd., Hong Kong, 1994 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Jeffrey Hantover was born and grew up in Kansas City, Missouri. He graduated from Harvard College, attended the John F. Kennedy School of Government and received a Masters in Sociology of Education and PhD in Sociology from the University of Chicago. He taught sociology at Vanderbilt University, was the director of a national social service agency in New York, and held senior positions in labor rights compliance for a major American clothing company. Jeffrey lived in Hong Kong for twelve years where he wrote on Asian art and culture. |

|

朱伟:历史的生活写照

韩杰

翻译:金石淑芬

当我提笔撰写此文时,距离香港回归中国刚好剩下一千个日子,这一整数将会在我们脑海里烙下深刻意义,而这倒数日子渐近,也意味着它的形势已较无止境的机场会议、联络小组会谈为强。此刻,我们都已自觉地生活在历史洪流中。当我们边数着日子,边做记号,也发现朱伟的作品,其受欢迎程度更远超乎假日的点心之上。朱伟就是一个倒读秒数计时的画家,和我们深处于共同的历史中,朱伟透过作品表达对面的祖国伸张双手,迎接我们(甜蜜的生活四号),身旁的儿童指出,一九九七年已在眼前。

朱伟是在去年广州“中国艺术博览会”上被发现。今年春在香港的“新向”亚洲艺术博览会上,宛如一颗明日之星崛起。无疑地,后八九中国新艺术展出成功之后,激发起人们对中国政治波普艺术的兴趣,一番清新、神秘的魅力也是吸引人的主因。然而作品本身更足以阐释这股抵挡不住的热潮,他的作品已在香港的末世年代中奏起文化心弦,悲观和乐观的情绪交织在每个人内心深处。

观赏朱伟的作品,若将画面文字和历史内涵略去,也能体会这些画深具意识在其中。朱伟不以市场导向来作画,他像个说书(故事)的,将道地的北京故事记录下来。我们想听他叙述故事,实在是他对自己比对我们更有兴趣地讲说故事。他从不推销,而我们却乐意接受,这也是非常矛盾的。

他所描绘的内容对香港人而言是苦乐参半的故事:我们一方面嘲笑那些夸张的诙谐的漫画人物,一方面却又紧握着身份护照和单程票。未来的香港同胞心想这些超大型的解放军过着甜蜜的生活,外表看似庞然大物,事实上也不过是木偶戏的傀儡罢了,一如西方导演卓别林的几个秃头、呆脑、大嘴人物造型,深具反嘲意味。

|

|

朱伟是当今国内风起云涌变化的一份子,艺术上的绘画、文学、电影正扩张私自领域并以评论和漠视向权威当局挑战。例如后八九部队大军,看似厚脸不逊,却在笔端露出一份温柔甜蜜来,处在这政治嘲讽的主流中,对马克斯主义和唯物主义也只是一种消极逃避的心态而已。朱伟是当今中国画坛上的忠实记录者,悄隐地将生活中幽默的一面表达出来,一如近来所作色情画,也只是含蓄意味。朱伟不期望开怀大笑,而盼望博得会心莞尔。 |

|

朱伟在多幅作品中,透过一个睁大双眼的女孩来观看周围熙熙攘攘的人群(例如:新编花营锦阵一号)。她那无知的眼神显露了这个帝王的率直、真实。年轻人炫耀的打扮,带着随身机朝向麦当劳快餐店,此店标榜服务至上。而一些官员们正吸啜着文明世界的可乐,享受甜蜜的生活。

朱伟的幽默和平易近人来自他艺术上的概括性,他没有树立敌人,没有他我之分,没有人可以指责,只是大家在一个平凡的世界,演出共同体会的时代喜剧。他是个善意的讽刺者,将内心的剖白和批判,广泛地释放出来,希望得到共鸣。他的作品并不是强硬派官员所指斥的“毒草”,而是足以迸裂独裁主义王国的杂草、墙草。

朱伟曾在人民解放军队中服务了十年,他将自己和同僚描绘成一脸无知茫然,他们并非新时代的栋梁,只是一些柔顺的支撑架,随波逐流,无所知从。

军队和老百姓都以平常心来看这个新世界,仔细观察画面上的人物,几乎没有人互相注视着对方或往外看我们,他们总是不经意的看着一边,或向上看,或向眼角外看,只有孩童们才会睁大眼睛,以天真好奇的眼神,直视这世界到底如何运转,然而只有外面的人知道这个答案:他们的生命剧本是由未知的人所写成的。

然而在我们会心一笑时,似乎也由朱伟的幽默中看出那丝丝的不安。那些机敏的人物似在聆听远处的辘声,以便及时抓紧风向,他们看似愚蠢,却毫不傻笨:快快发财,快快享受,开设外币户口,祈求事事顺利。他们较西方投资者更聪明,以快速直线的信心分析情势,因为他们知道政治的风向随时会有所改变,今天一件无心之事都可法成为明天受迫害的举证。

朱伟以赭、绿等色彩来描绘新中国市场社会主义入侵古老的北京生活,使画面看似褪色的壁报,又像古老年代的壁画。这媒介多少也带着讯息:以一种怀旧之情平叙当今的新世界,既不喜欢,也不责备,朱伟只是以一种不在意的心态,半微笑似的迎接新中国的来临。

998和计时中

一九九四年十月六日

首次刊发于Plum Blossoms国际有限公司1994年于香港出版之《朱伟-北京故事》,第16-19页 |

|

韩杰,出生成长于美国密苏里州的堪萨斯城。毕业于哈佛大学,曾就学于约翰·F·肯尼迪政府学院,获芝加哥大学教育学硕士学位,及该校的社会学博士学位。曾任教于范德堡大学社会学系,并担任位于纽约的全国社会公益服务理事会董事。在香港居住过十二年,撰写过多篇亚洲艺术和文化的文章。 |

|

|