L'OFFICIEL Art 《艺术财经》杂志

November 2013 二零一三年十一月

|

L'OFFICIEL Art 《艺术财经》杂志 November 2013 二零一三年十一月 |

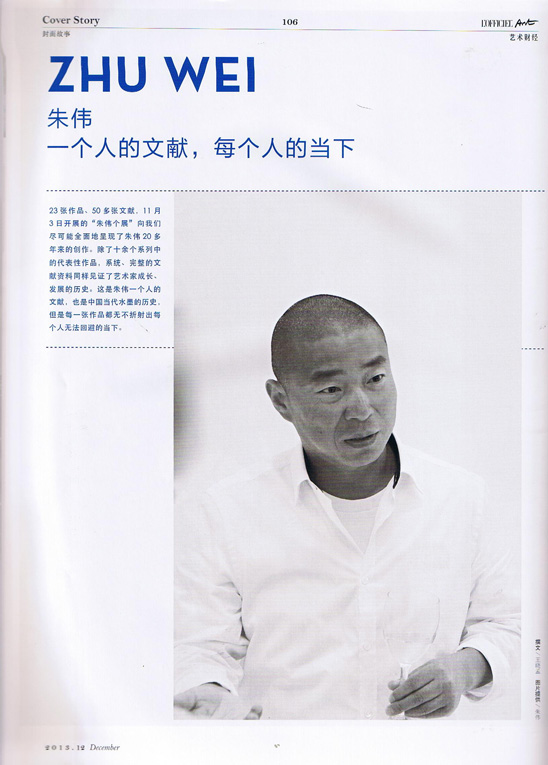

第108页: (本页上部左图) “朱伟故事”,《B国际》月刊,1995年3月 (本页上部中图) “在万玉堂的朱伟”,Joan Lebold Cohen撰文,《亚洲艺术新闻》双月刊,1995年3/4月 (本页上部右图) “反叛,全为自己的原因”,Angelica Cheung撰文,香港《东方快报》,1994年11月14日 《北京故事》(1993-1995年) 《北京故事》的创作与20世纪80年代中国大地上掀起的思想解放运动有关,军队和知识分子这两个不同角色在这场运动中发挥了各自不同的作用。1989年时的艺术家,作为军队中的一员,正处于意气风发的青年时代。军队森严的纪律在朱伟心中留下了不可磨灭的记忆,以及对自由更为强烈的感触。知识分子追求自由解放思想的特质,也在同朱伟一样的年轻人心中萌发。《北京故事》可以看作是朱伟寻求自我意识被认同的宣泄,含蓄内敛的个性决定了朱伟倾向于幽默,而不是选择极端的视觉表达方式,在此之前朱伟受到的多年的传统文化素养的浸染,也极大提升了作品中沉淀的深层寓意的力量。 基于个人的特殊经历,朱伟成功地创造了光头军人、大红旗、五角星、格子窗、芭蕉叶等具有个人特点的艺术符号,并让这些符号很好地转换为具体的形式。应该说,这是新题材与新感受——包括“社会主义经验”进入传统程式,继而改造传统程式的过程,其结果又自然的影响了画面大的结构与处理方式。尽管在现代生活与西方现代艺术的启示下,他也加进了一些新的手法,但他仍然是在传统的作画程序中操作,运用的也主要是中国画颜色。由于他画中的色彩是通过色墨交混的多次渲染而成,所以既具有薄中见厚、深沉耐看的效果,也具有与西画完全不同的艺术感觉。 ——《中国当代艺术史:1978-1999》,鲁虹著,上海书画出版社2013年出版 (本页下部左上图) “来自香港、广州、北京三地的报导”,Susan Dewar 撰文,《Orientations》月刊,1994年2月 (本页下部左下图) “中国艺术中的喜悦和利润”,Meredith Berkman撰文,《时代周刊》,1997年9月1日 (本页下部右上图) “朱伟之展览”,《亚洲艺术报》2001年1月 (本页下部右下图) 《国际亚洲艺术博览会1997》,纽约国际亚洲艺术博览会有限公司出版,纽约第七军械库,1997年3月 1988-1992年 从20世纪80年代后期开始,中国水墨画开始了现代变革的潮流,最初的诱因在于饱受古典传统影响的水墨画家面对迅速变化的中国社会,他们的内心情感和现实境遇都已不同于古典大师,传统久远已与现代不谐,中国画自身需要更多样性的拓展来回应社会的巨变。1988年朱伟仍是一名在校学生,画家自己收藏的多幅创作于这个阶段的作品,虽以“仿八大”命名,但已经初显此后作品风格的端倪,酝酿着此后重要代表作品《北京故事》的雏形。 《上尉同志》(1992-1994年) 朱伟从1992年开始创作《上尉同志》,此时的他刚刚脱离部队系统。此前他所经历的十余年的军旅生活是他最为熟悉的,并给他留下了永不磨灭的记忆,也在职业生涯的最初成为他绘画的灵感来源。《上尉同志》是朱伟最早用中国水墨传统技法寻找当代现实表达的肇始,他创造的“上尉同志”无疑对主题性绘画中的军人形象是一个颠覆。自此开始,朱伟的艺术生涯迈出了重要一步,并且在笔法、纸张、设色、造型等方面开始了持续的探索,在中国国内水墨界还在为笔墨问题困惑和争论不休的时候,朱伟已经用实际行动开始了水墨当代化的探索之路。 p.108: (Upper Left) “The Story of Zhu Wei”, B International, March 1995 (Upper Middle) “Zhu Wei at Plum Blossoms” by Joan Lebold Cohen, Asian Art News, March/April 1995 (Upper Right) “Rebel with a cause that is all his own” by Angelica Cheung, Eastern Express, Hong Kong, November 14th 1994 The Story of Beijing (1993-1995) The creation of The Story of Beijing has connections with the liberating movement of thought that emerged in China during the 80’s; in which the army and intellectuals had different roles to play. The artist in 1989, as a member of the army, was at his daring and energetic prime. The highly disciplined experience from that time left its mark on Zhu, who consequently began to hold strong reflections on freedom.? The quality of how the intellectual craves for free thoughts is reflected in those of Zhu’s generation. The Story of Beijing can be considered as Zhu’s search for the acknowledgement of his self-consciousness.? A subtle personality has made Zhu’s artistic expression humorous, rather than radically visual in its approach.? Moreover, the fact that Zhu has amassed years of training in classical cultures also enriches the inner symbolic power of his work. Zhu successfully created art signs with personal characteristics like bald soldier, red flag, five-pointed star, latticed window and banana leaf based on his special experiences. He also transformed those signs into specific forms. We can say this is the process during which new subjects and feelings, including “socialist experience” went into traditional form and then got updated, which naturally affected paintings’ structural and process methods. Inspired by modern life and western modern art, Zhu added new techniques, but he still worked within traditional painting procedures and mainly used colors of Chinese paintings. Because Zhu applied those colors with ink by multiple times, the visual effects totally differ from western paintings—they have layers and a lingering charm. ——THE HISTORY OF CONTEMPORARY CHINESE ART FROM 1978 TO 1999 by Lu Hong, Published by Shanghai Literature & Art Publishing House in 2013 (Bottom Upper Left) “Report from Hong Kong, Guangzhou and Beijing” by Susan Dewar, Orientations, February 1994 (Bottom Below Left) “The pleasures and profits in Chinese art”, Meredith Berkman, Time magazine, September 1st 1997 (Bottom Upper Right) “Zhu Wei Exhibition”, The Asian Art Newspaper, January 2001 (Bottom Below Right) THE INTERNATIONAL ASIAN ART FAIR 1997, published by The International Asian Art Fair Ltd., The Seventh Regiment Armory, New York, March 1997 1988-1992 Around the late-eighties, Chinese ink painting witnessed a modern renaissance. Initially, the incentive for this shift came from a group of traditionally trained ink painters who were experiencing the rapid changes happening in China at the time. They had come to realize that their feelings and surroundings had become drastically different from those of their predecessors. Traditions and values from the past no longer applied harmoniously to the contemporary world. Thus, Chinese painting required diverse developments to respond to the radical changes that were occurring within society. In 1988, Zhu Wei was a student. Today, he still owns many of his paintings from that period. Although most of those works were copies of other paintings, they already began to show the style Zhu Wei would employ in his future important works, such as “The Story of Beijing”. Comrade Captain (1992-1994) Zhu Wei began the Comrade Captain in 1992 after leaving army. The experience of more than 10 years in the army left an indelible memory, which became a source of inspiration. Comrade Captain marks the beginning of how Zhu attempts to express contemporary reality through classical Chinese ink techniques. The image, “Comrade Captain” that Zhu has created is a subversive version of the subject matter. Since then, the artist has leaped a step forward in his career and he continues to explore the use of brush, paper, colours and forms. At a time when the use of ink and brush was still a complex and a heated debate for the Chinese, Zhu had already embarked on his journey of investigation. |

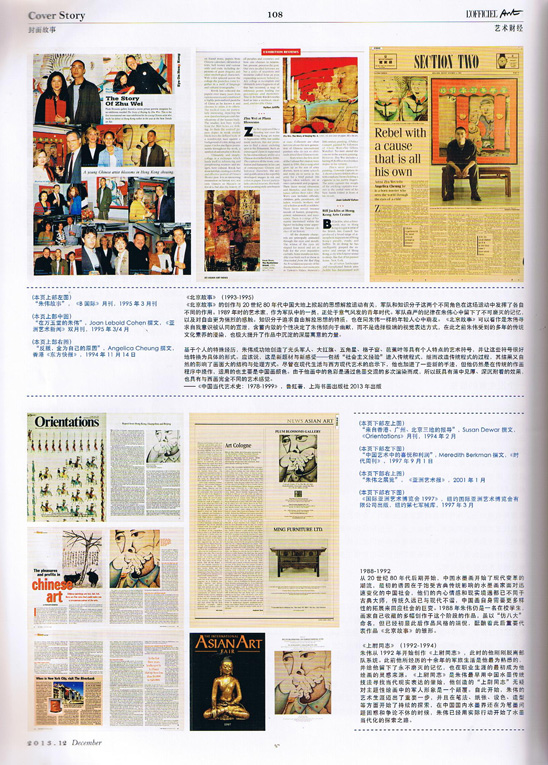

第109页: (本页上部左图) 广场九号 纸本水墨 192 x 193 cm 1995 海外私人藏 (本页上部右图) 封面故事“艺术进攻:当代中国艺术能生存吗?”,Scarlet Cheng撰文,《Asia Magazine》,1996年8月16日 《广场》(1995-1996年) 1995年到1996年间,朱伟创作了关于天安门广场的海洋式绘画。朱伟不是用诗,而是用著名的摇滚乐领袖崔健的歌词《解决》作为文本,“明天的问题很多,可现在只有一个;我装作和你谈正经的,可被你看破;你好象无谓的笑着,还伸出了手;把我的虚伪和问题一起接受。”在这里,朱伟将他认为已经与现实社会脱离关系的中国传统绘画方式和与现实社会联系紧密的流行文化结合起来。崔健大胆的歌词被以汉代竹简式的书写方式填写于画面中,用军人的形象和蓝绿色调的背景相结合,这幅画可以看作是朱伟另一种自我形象的反映。 在一个强调艺术创新与个性表达的新时代,朱伟在“创”与“守”之间保持了很好的张力,这很值得同道借鉴。他的启示是:在寻求对于当代生活的表达时,重要的是要努力沿续传统的表达方式,并有所创造、有所丰富。而在当代艺术有着全球同质化发展的情况下,这种保持异质化表达的追求不是显得特别重要吗?——鲁虹《中国当代水墨:1978-2008》,文化艺术出版社2013年出版 (本页下部左图) 香港、新加坡万玉堂画廊展览手册,2000年10月11日 (本页下部中图) 甜蜜的生活二十一号 纸本水墨 178 x 170 cm 1998 尤伦斯夫妇藏 (本页下部右上图) 中国日记五十二号 纸本水墨196 x 265 cm 2001 美国威廉姆斯大学美术馆藏 (本页下部右下图) 无题四号 纸本水墨 190 x 132 cm 2002 广州艺术博物院藏 《大水》(2000-2001年) 《大水》是与《中国日记》属于同一类的尝试,风景是对现实的隐喻。繁密的水波一浪推一浪,朱伟一直将古代的巅峰画家视为故知,并希望对他们缔造的传统能够有所突破的继承,因此朱伟在吸收传统艺术的精髓方面下足了工夫,不仅是没骨工笔画,还旁及中国古代画论,中国青铜器,书法篆刻,纸张工艺等,观众从画面上可以考察出深厚的东方文化传统底蕴,例如作品构图有篆刻般的谨严精密,人物造型有青铜器的古朴稳重,线条造型有瓷器轮廓的那种圆润与简洁,画面肌理效果经过反复处理后呈现出凝重浑厚,所以看朱伟的作品,人们可以感觉到他对传统文化精髓的把握和精神气质的提炼。 《中国日记》(1995-2002年) 《中国日记》似乎是朱伟宣泄生命中古典情结的一个出口。在这个作品中,朱伟没有更多的表现人物题材,而是怀着对传统文化精髓的崇敬和偏爱,与韩滉、赵诘、李嵩等进行超时空对话。某种程度上,朱伟对古典绘画的理解,比秉持着正统观念的所谓权威们来得更纯粹和深刻。他坚定地认为今天发生的一切,都可以在传统中找到原型,这成为他援引古典的思想基础,而这也的确是历史与当下的本来联系。 p.109: (Upper Left) The Square No.9 ink and color on paper 192 x 193 cm 1995 private collection (Upper Right) Cover story “Art Attack:Will Contemporary Chinese Art Survive?” by Scarlet Cheng, Asia Magazine, August 16th 1996 The Square (1995-1996) From 1995-1996, Zhu Wei produced “oceanic” paintings to relate to Tiananmen Square. Instead of using poetry, Zhu takes Cui Jian’s lyrics Solution as the text to accompany his work: “Heaps of problems lay before me, but now there is only me. I pretend to be serious with you, but you see through me. You extend your arms with seeming indifference, accepting all my sham and trouble.” Here, Zhu takes what he thinks to be disconnected to the contemporary reality: the classical painting technique combined with pop culture--something that is tightly tied to contemporary society. As Cui’s bold lyrics-- written in the Han Dynasty bamboo slip style of calligraphy-- fill the picture with a symbolic military coloured (green and blue) background, the work can thus be seen as another one of Zhu’s personal mirror images. In an era stressing art innovation and personal expression, Zhu set a good example by striking a balance between “creation” and “inheritance”. From Zhu, we learned that it’s crucial to inherit traditional expression methods while seeking expressions of contemporary life and make creations to enrich them. Isn’t the heterogeneous expression especially important given the global homogenous development of contemporary art? ——CONTEMPORARY CHINESE INK PAINTING FROM 1978 TO 2008 by Lu Hong, Published by Culture and Art Publishing House in 2013 (Bottom Left) Pamphlet of Gallery Events, published by Plum Blossoms (International) Ltd., Hong Kong and Singapore, October 11 2000 (Bottom Middle) Sweet Life No.21 ink and color on paper 178 x 170 cm 1998 Mr. and Mrs. Ullens Collection (Bottom Upper Right) China Diary No.52 ink and color on paper 196 x 265 cm 2001 Williams College Museum of Art Collection, MA, USA (Bottom Below Right) Untitled No.4 ink and color on paper 190 x 132 cm 2002 Guangzhou Art Museum Collection Great Water (2000-2001) Great Water is a similar to the China Diary in that the landscape becomes a metaphor of reality. The dense waves at the back are always pushing forward, just as Zhu has always seen ancient masters as old friends and he wishes to make a breakthrough to their convention. Hence, he has made an effort to absorb the essence of the tradition, including the mo gu gong bi hua (the boneless brush fine line painting), Chinese ancient aesthetic theory, Chinese bronze, seals and calligraphy and paper craftsmanship. Viewers can therefore see the rigorous composition like seal carvings; the sober model of smoothness from porcelain features; the natural textures coming from the repeated treatment, which all capture the spirit of tradition. China Diary (1995-2002) China Diary is a channel for Zhu Wei to unleash his affection towards Chinese antiquity and the classics. In this work, Zhu has not presented much of the human subject, but his admiration and preference for the essence of traditional culture. And he has developed a dialogue beyond time and space with Chinese masters such as Han Huang, Zhao Jie and Li Song in his paintings. To a certain extent, Zhu’s understanding of classical paintings is more profound and pure when compared to the so-called authorities that only comply with the orthodox. The artist persists that whatever happens today can be traced back to tradition. This rationale has become his foundation of referring to the classics. Indeed, Zhu’s notion has captured the initial linkage between history and the contemporary. |

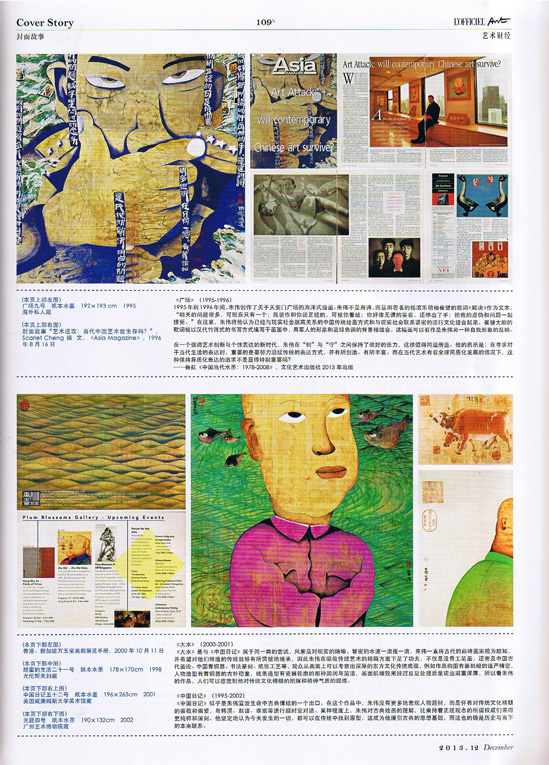

第110页: (本页上排中图) “朱伟:追求‘简单’”,Alexandra A. Seno撰文,《国际先驱论坛报》,2005年12月3/4日周末刊 (本页上排右图) “今日水墨”,吴子茹撰文,英文《环球时报》2010年7月14日 (本页下排左图) “朱伟谈艺术及中国”,Ulara Nakagawa撰文,日本《外交学者》网the-diplomat.com,2011年5月2日 (本页下排中图) 开春图十五号 纸本水墨 160 x 120 cm 2008 海外私人藏 (本页下排右图) 无题一号 纸本水墨 234 x 197 cm 2002 上海美术馆藏(粉本) 朱伟是第一位将工笔画手法引进中国当代艺术领域的艺术家。当大量的中国新锐艺术家用油画来做“政治波普”和“讽刺现实主义”作品时,他便开始探索传统的工笔画来表现当代中国的政治生活的可能性,完成了有代表性的系列作品。他的作品已经与传统的工笔水墨画产生了巨大的差距,但在设色、勾勒、晕染等技术层面保持了基本的特征。他作品的传统语言与当代政治生活图景之间的反差使作品获得了难以抗拒的吸引力。 ——《再水墨:2000-2012中国当代水墨邀请展》,傅中望主编,湖北美术出版社2012年12月出版 朱伟是一个有着非常巨大的脑袋的小个子男人。作为中国现代艺术“大脑袋(自大)运动”的先驱之一,这个生于北京的艺术家描绘了有着泡泡般巨大脑袋的人们的肖像,他们不成比例的庞大脑袋不仅充斥着巨幅画框,也充斥着--如果我们可以比喻的话--他们的世界。曾梵志,湖北省武汉人,描绘了中国人口聚集的都市中正在寻找身份的失落灵魂,他们时髦的衣服映衬着麻木的神情,在大城市里适应生存。这些肖像是对中国个人超越集体现象的一种自省和庆祝。“只有把注意力放到个人身上,才能在中国找到真正的天才”,赵能志说,他是一个居住在四川省成都市的大脑袋。然后,走过阴沉的街道,街道上那些没有性格的水泥盒子已经吞没了传统的木头搭建的茶馆,赵又说道:“我们居住的这个国家正迫切地需要一点点天分。” ——“生而巨大——中国当代艺术的新浪潮”,Hannah Beech撰文,《时代》周刊2002年11月11日封面系列报道“中国文化新革命(4):‘酷’之诞生” 朱伟在新技法上所做的思考和尝试,比评论家关心的主题或概念上要多,但他知道仍然有许多问题无法解决,比如表现人物的正面——他无法以水墨去画张晓刚的《大家庭》那样的作品。作为水墨改良的坚持者,他不停地感叹水墨表现力的“弱”:“画人,水墨必须画一个完整的人,油画不用。因为水墨讲线条,色彩是辅助的——人身上哪有线条?”也因此,他最想描摹的人物心理,就更难实现了。朱伟的水墨新花样能否使中国画传统技法产生新的活力,尚难断言。但有一点朱伟很明白:“画传统水墨,50岁之前根本出不来。” ——“波普?油画?花样水墨”,李宏宇撰文,《南方周末》,2006年5月4日 《乌托邦》(2001-2005年) 2000年以后,朱伟创作的多个主题都成为其代表作。著名的《乌托邦》刻画了那些顶着大脑袋的强健身躯参加官方会议的情景。因为朱伟曾多次忍受这样的会议,所以他的笔触是具有同情心的——他知道要挣扎着保持注意力到底是什么含义。巨大的红色旗帜和繁花似锦的讲台摆设是这种正式群众聚会场合不可避免的;而从古代册页里移植过来的折枝、花篮,这些具有象征性的元素,则很好地担任了现代宫廷的隐喻。 朱伟的过人之处就在于:既很好地继承了传统工笔画的表现程式,又用新的题材、新的观念、新的感受重构了工笔表现的新传统,这不仅使他能从容自如地进行全新的艺术表现,而且还使画面具有平面化、装饰化的特点。在本作品中,背景是会议主席台上的红旗与树木,前景是从宋代画家李嵩册页里借用来的花篮,中景则是出席会议的代表,只见他们一面恭敬地在听着大会发言,一面还时不时地用粗短的钢笔记录着什么。而当它们并置在一起时,便形成了人们司空见惯的场面。 ——《中国当代艺术三十年1978-2008》,鲁虹著,湖南美术出版社2013年出版 《开春图》(2005-2008年) 《开春图》是朱伟自2005年至2008年间主要创作的作品,在这一作品中,画面构图汲取了一些中国粉彩瓷器的图案,画面被错落有致的小人布满。同时朱伟在《开春图》的创作中,对画作表面的水洗以及进一步处理延续了他一贯的技法,在勾画头发和眼睛前对宣纸的小心揉搓和水洗,使颜色褪变得微妙而天然。《开春图》作品的创作,成为朱伟艺术创作一个新阶段的开始,世俗化的表达和戏谑的内涵,淡化了意识形态的表态,而更多了人情味道和生活的姿态,同时朱伟对中国文学、诗词等传统文化的研习,也使得最近的《开春图》多了几分古色古香的气质。 p.110: (Upper Middle) “Zhu: Looking for ‘Something Simple’”, Alexandra A. Seno, International Herald Tribune, December 3/4 2005 (Upper Right) “Ink Painting Today” by Wu Ziru, English version of Global Times, July 14 2010 (Bottom Left) “Zhu Wei: On Art & China” by Ulara Nakagawa, The Diplomat website the-diplomat.com, Japan, May 2 2011 (Bottom Middle) Vernal Equinox No.15 ink and color on paper 160 x 120 cm 2008 private collection (Bottom Right) Untitled No.1 ink and color on paper 234 x 197 cm 2002 The colorful sketch (fen ben) of the piece is collected by Shanghai Art Museum Zhu Wei is the first artist adopting meticulous (gong-bi) ink painting language into Chinese contemporary art scene. When many Chinese new artists were working on “political pop” and “ironic realism” oil paintings, Zhu was exploring the possibility to reflect contemporary Chinese political and social life with traditional meticulous ink and wash, and had completed representative series. His motifs differentiate his art from those traditional meticulous ink paintings, however, the techniques Zhu employed, such as coloring, outlining, blending and other, still remain the fundamental characteristics of traditional. The dramatic contrast between traditional art language and contemporary political social motifs makes his art irresistibly appealing. ——RE-INK: INVITATION EXHIBITION OF CONTEMPORARY INK AND WASH PAINTING 2000-2012, edited by Fu Zhongwang, published by Hubei Fine Art Publishing House, December 2012 Zhu Wei is a diminutive man with a very large head. One of the progenitors of modern Chinese art's "big head movement," the Beijing-based artist paints portraits of bubble-headed people, their gargantuan proportions stretching the confines of both his giant canvases and, if we must get metaphorical, their worlds. Zeng Fanzhi, a native of Wuhan in Hubei province, central China, paints lost souls struggling for identity in China's thronging metropolises, their fashionable clothes juxtaposed with the cauterized expressions people adopt to survive in big cities. Such portraits are introspective, whimsical celebrations of a China in which the individual can triumph over the group. "It's only by focusing on the individual that we can find real talent in China," says Zhao Nengzhi, a big head who lives in Chengdu in central Sichuan province. Then, walking glumly down streets where wooden teahouses have been replaced by characterless, concrete boxes, he adds, "We live in a country that desperately needs a little genius." ——“Living Large-China new wave of modern art” by Hannah Beech, Time magazine, November 11th 2002, cover story “China’s Next Cultural Revolution (4) - The Birth of Cool” The thinkings and experiments Zhu Wei has put in the new techniques are much more than subjects and concepts that the critics are concerned, as he knows that there are still many problems unsolved. For an example, the frontal face of a figure - he can never use ink and color to paint a work like Zhang Xiaogang’s Big Family. As a holdout of ink and color melioration, he keeps sighing on the “weakness” of expressive force of ink and color: “Painting a figure, with ink and color you have to paint a figure at the full length, with oil painting it doesn’t have to. Because ink and color stresses on lines, color is only auxiliary - but where are the lines on a human body?” For the same reason, it is even more difficult to realize his ideal of draw human mentality. Whether if Zhu Wei’s new ink and color can revitalize the traditional techniques of Chinese Painting is yet to be proved. But there one thing Zhu Wei is aware of: “Do Chinese ink and color, don’t even think about success before 50.” ——“Pop? Oil Painting? New Ink and Color” by Li Hong-yu, Southern Weekend, May 4th 2006 Utopia (2001-2005) After 2000, Zhu produced several representational themed works. The renowned Utopia depicting the scene where big-headed masculine men are attending an official conference, is one of them. Having attended countless conferences like this, the artist is sympathetic to the poor participants for he knows the struggle of keeping one’s concentration. The large red flag and a flowered stage are also inevitable props in a formal assembly. Also, plants taken from a classical album provide the picture with a modern palace setting. Zhu Wei’s strength lies in his ability to integrate traditional Gong-bi technique and new subjects, ideas and feelings. It enabled him to freely exhibit new art forms with more plane turns and decorations. In this work, red flag and trees on the podium dominated the background, the foreground displayed flower baskets borrowed from the painting album of Lin Song (a painter in Song Dynasty), and the middle-ground showed representatives at the meeting, who take notes with short and thick pens while listening attentively. When combined together, it formed a usual image. ——THIRTY YEARS OF CONTEMPORARY CHINESE ART FROM 1978 TO 2008 by Lu Hong, Hunan Fine Arts Publishing House, 2013 Vernal Equinox (2005-2008) The Vernal Equinox was Zhu Wei’s major creative project during 2005-2008. In this works, the composition of the painting draws reference from the image of the classical Chinese famille-rose porcelains. Filling the picture with interspersed little human figures, Zhu adds his own touch to these works with his trademark classical ink wash style. In the areas around the hair and the eyes of the human figures, he carefully rubs and washes on the xuan paper, causing colours to fade with a sense of delicacy and naturalness. The Vernal Equinox in 2005 marks a new beginning for Zhu. By adopting a more down to earth expression and a comical context, his direct response to ideology becomes less explicit. What is more apparent now is his concern for humanity and one’s living conditions. At the same time, the artist’s studies of traditional Chinese culture, such as Chinese literature, poetry and lyrics also lend the Vernal Equinox a taste of Chinese antiquity. |

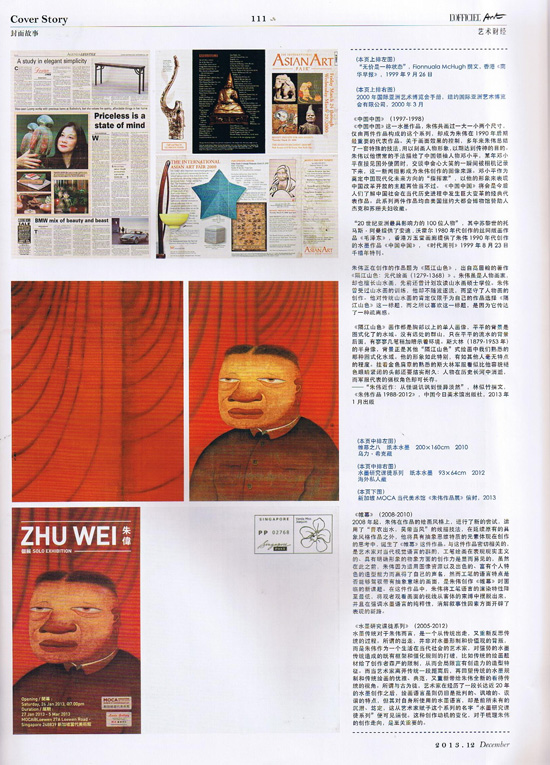

第111页: (本页上排左图) “无价是一种状态”,Fionnuala McHugh撰文,香港《南华早报》,1999年9月26日 (本页上排右图) 2000年国际亚洲艺术博览会手册,纽约国际亚洲艺术博览会有限公司2000年3月出版 《中国 中国》(1997-1998年) 《中国 中国》这一水墨作品,朱伟共画过一大一小两个尺寸,仅由两件作品构成的这个系列,却成为朱伟在90年后期最重要的代表作品。关于画面效果的控制,多年来朱伟总结了一套特殊的技法,用以刻画人物形象,以期达到传神的目的。朱伟以他惯常的手法描绘了中国领袖人物邓小平,某年邓小平在接见国外使团时,交谈中会心大笑的一瞬间被相机记录下来,这一新闻摄影成为朱伟创作的图像来源。邓小平作为奠定中国现代化未来方向的“指挥家”,以他的形象来表现中国改革开放的主题再恰当不过。《中国 中国》将会是今后人们了解中国社会在当代历史进程中发生巨大变革的经典代表作品。此系列两件作品均由美国纽约大都会博物馆赞助人杰克和苏珊夫妇收藏。 “20世纪亚洲最具影响力的100位人物”,其中苏黎世的托马斯·阿曼提供了安迪.沃霍尔八十年代创作的丝网版画作品《毛泽东》,香港万玉堂画廊提供了朱伟九十年代创作的水墨作品《中国 中国》,《时代周刊》1999年8月23日千禧年特刊 朱伟正在创作的作品题为《隔江山色》,出自高居翰的著作《隔江山色:元代绘画(1279-1368年)》。朱伟虽是人物画家,却也擅长山水画,先前还曾计划攻读山水画硕士学位。朱伟曾受过山水画的训练,他却不随波逐流,而坚守了人物画的创作。他对传统山水画的肯定仅限于为自己的作品选择《隔江山色》这一标题,而之所以喜欢这一标题,是因为它传达了一种疏离感。《隔江山色》画作都是胸部以上的单人画像,平平的背景是图式化了的水域。没有远处的群山,只在平平的流水的背景后面,有寥寥几笔稍加暗示着环境。斯大林(1879-1953年)的半身像,背景正是其他“隔江山色”式绘画中我们熟悉的那种图式化水域。他的形象如此特别,有如其他人毫无特点的程度。挂着金色肩章的熟悉的斯大林军服看似比他容貌褪色眼睛紧闭的头部还要结实耐久:人物在历史长河中消逝,而军服代表的强权角色却可长存。 ——“朱伟近作:从怪诞讥讽到怪异淡然”,林似竹撰文,《朱伟作品1988-2012》,中国今日美术馆出版社2013年1月出版 (本页中排左图) 帷幕之八 纸本水墨 200 x 160 cm 2010 乌里·希克藏 (本页中排右图) 水墨研究课徒系列 纸本水墨 93 x 64 cm 2012 海外私人藏 (本页下图) 新加坡MOCA当代美术馆《朱伟作品展》信封,2013 《帷幕》(2008-2010年) 2008年起,朱伟在作品的绘画风格上,进行了新的尝试,运用了“曹衣出水,吴带当风”的线描技法,在延续原有的具象风格作品之外,他将具有抽象思维特质的元素在体现在创作的思考中,诞生了《帷幕》这件作品。与这件作品密切相关的,是艺术家对当代视觉语言的斟酌,工笔绘画在表现现实主义的、具有明确形象的物象方面的创作力是显而易见的,虽然在此之前,朱伟因为运用图像资源以及出色的、富有个人特色的造型能力而赢得了自己的声名,然而工笔的语言特点是否能够驾驭带有抽象意味的画面,是朱伟创作《帷幕》时面临的新课题。在这件作品中,朱伟将工笔语言的渲染特性降至最低,将观者观看画面的视线从客体的束缚中摆脱出来,并且在强调水墨语言的纯粹性,消解叙事性因素方面开辟了表现的新路。 《水墨研究课徒系列》(2005-2012年) 水墨传统对于朱伟而言,是一个从传统出走,又重新反思传统的过程。所谓的出走,并非对水墨形制和价值观的背叛,而是朱伟作为一个生活在当代社会的艺术家,对强势的水墨传统造成的既有框架和僵化规则的打破,比如传统的绘画题材给了创作者森严的限制,从而会局限富有创造力的造型特征。而当艺术家离开传统一段距离后,再回望传统的水墨规制和传统绘画的优雅、典范,又重新带给朱伟全新的看待传统的视角。所谓与古为徒,艺术家在经历了一段长达近二十年的水墨创作之后,绘画语言虽则仍旧是批判的、讽喻的、诙谐的特点,但其对自身所使用的水墨语言,却是前所未有的沉潜、笃定,这从艺术家赋予这个系列的名字“水墨研究课徒系列”便可见端倪。这种创作动机的变化,对于梳理朱伟的创作走向,是至关重要的。 p.111: (Upper Left) “Priceless is a state of mind” by Fionnuala McHugh, South China Morning Post, Hong Kong, September 26th 1999 (Upper Right) The International Asian Art Fair 2000 Brochure, published by The International Asian Art Fair Ltd., New York, March 2000 China, China (1997-1998) The ink painting series China, China consists of one big and one small-scale work by Zhu Wei.? Although the series only contains two pieces, it has been the one of the most crucial works in Zhu’s career during the late 90’s.? Concerning the control of the pictorial surface, Zhu spent years perfecting his unique technique: paper is painted in yellow on top of a rough plank or carpet, resulting in interesting patterns in the concave areas when the ink dried.? Zhu also draws his inspiration from the journalistic picture that captures the laugh of Chairman Deng Xiaoping while receiving a group of diplomats.? It is especially witty of Zhu to use Deng, the “conductor” of the future for modern China as a symbol for China.? However, Zhu does not demean or mock the meaning of the subject matter; he reinforces it with the extensive use of red and yellow and thus brings about a profound effect. “The most influential 100 Asians of the 20th century”, with “Mao” by Andy Warhol, courtesy Thomas Ammann from Zurich, and “China China” by Zhu Wei, courtesy Plum Blossoms International Ltd., Time magazine, the special issue for the coming millennium, August 23 1999 The title of Zhu Wei’s ongoing works, Hills Beyond a River, is taken from James Cahill’s book, Hills Beyond a River: Chinese Painting of the Yüan Dynasty, 1279-1368. Although Zhu is a figure painter, he is also an adept landscape painter, and long ago had aimed to complete a master’s degree in landscape painting. Although he has the training to create landscapes Zhu Wei has not chosen to participate in this trend, keeping to the genre of figure painting. His nod to historical landscapes is restricted to the title Hills Beyond a River, which he likes because it conveys a sense of alienation. Paintings in Zhu Wei’s Hills Beyond a River each portray a single figure from the chest up, against a flat background of patternized water. There is no distant group of hills, and only a few bear any hint of a setting beyond the flat background of flowing water. The bust portrait of Joseph Stalin (1879-1953) is backed by the patternized water familiar from other Hills Beyond a River paintings. His image is as particular as the other figures are nondescript. Stalin’s familiar uniform with gold epaulettes seems more solid and lasting than his head, whose feature are faded, and eyes closed: the individual fades in history, but the powerful role represented by the uniform endures. ——“Zhu Wei’s Recent Work: From Strange and Sardonic to Strange and Bland” by Britta Erickson, ZHU WEI WORKS 1988-2012, published by China Today Art Museum Publishing House, January 2013 (Middle Left) Curtain No.8 ink and color on paper 200 x 160 2010 Uli Sigg Collection (Middle Right) Ink and Wash Research Lectures Series ink and color on paper 93 x 64 cm 2005-2012 private collection (Bottom) Envelope for the solo exhibition “ZHU WEI WORKS” in Singapore Museum of Contemporary Arts (MOCA), 2013 Curtain (2008-2010) From 2008 onward, Zhu Wei made new attempt in his painting style; besides his continuation of figurative style, he represented abstract elements in his meditation in creation and gave birth to the new works of “Curtain”. It is the artist’s deliberation of contemporary visual language that is closely related with this works; the creativity of fine brush painting in representing realistic objects with clear image is obvious, although before this, Zhu Wei gained his reputation in his utilization of image resources and outstanding modeling capability of personal characteristics; however, the linguistic feature of fine brush painting is whether one can control pictures with abstract significance and this is the new issue faced by Zhu Wei in his creation of “Curtain”. In the works, Zhu Wei reduced the rendering characteristics of fine brush languages to the lowest and freed the eyesight of viewers on pictures from the restrict of the objects and he emphasized the purity of ink and wash language, opened a new way of representation in dissolving narrative factors.? Ink and Wash Research Lectures series (2005-2012) For Zhu Wei, ink and wash tradition is a process of leaving tradition and then reflect tradition again. The so called leaving does not mean a rebellion against the form and value of ink and wash, but rather, the breakthrough of existing framework and rigid rules established by powerful ink and wash tradition, such as the strict limits of traditional painting subjects which will limit the creative modeling characteristics, by Zhu Wei as an artist living in contemporary society. Yet when the artist keeps a distance from the tradition and then looks back to the rules of traditional ink and wash as well as the elegance and quintessence of traditional painting, a brand new perspective towards tradition will be brought to Zhu Wei. The so called being an apprentice with the ancient means that, thought the painting language of this artist after he experienced a 20 years ink and wash creation is still critical, allegorical and humorous, yet he shows his unprecedented calm and sincere attitudes towards his ink and wash language, which can be seen in the title “Ink and Wash Research Lectures series”. The variation of this kind of creation motive is vital for Zhu Wei to make clear his creation direction. |