|

|

|

Using

the Past to Serve the Present

--Traditional

Elements in the Art of Zhu Wei

Alfreda Murck

Zhu Wei is famously a painter of political and social subjects who

regularly draws on motifs from traditional Chinese painting. He

juxtaposes ancient and unmistakably modern figures to offer reflections

on Chinese life and society from the perspective of the era of reform

and opening that began in the early 1980s. He also works with

traditional media, but evolved his own ways of using them. There are

clear connections to the period of the Cultural Revolution and

quotations from the art of the imperial past marshaled to tell stories

of the more recent past. The mood is gently ironic. Cadres in their Mao

jackets and motifs from Song or Yuan dynasty paintings seem equally

distant in both being part of history. Zhu Wei’s art reflects a

culture and society that have changed dramatically, so that the

questions of what is enduring, and how we are to understand the recent

past come to the fore.

|

|

Zhu Wei’s most recent work is a series of paintings under the title

“Vernal Equinox,” which carries his art in a new direction. In

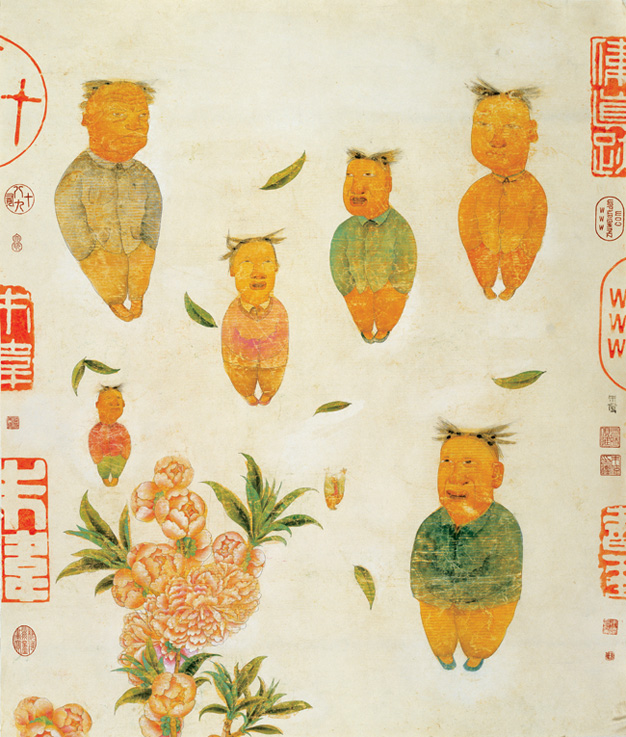

“Vernal Equinox No. 3” (Fig.

1)

weightless figures levitate against an undefined ground amid flowers and

leaves. Their faces are impassive, but variously register glum

indifference, distress, surprise, or satisfaction. Hands are tucked into

pockets or folded into sleeves recalling the idea of passively

“looking on with folded arms.” Scale varies, but not

consistently enough to indicate recession or space. Hair whooshes

up as though the figures are dropping, or blowing in the breeze like

seeds of germinating trees. Looking rather like untethered balloons, the

figures are unconnected, neither looking at each other or at us. |

Fig.1 |

| At

the lower left, a branch of peach blossoms in luxuriant bloom is larger

than any of the figures and anchors the painting. This is a quotation

from an anonymous small round fan of the Southern Song (960-1278), here

painted much larger and on paper instead of silk (Fig.

2).

On the left and right borders are impressions of large seals, deployed

in the manner of collectors’ inventory seals, half on the painting and

half on a now-missing mounting. One legend is “www,” an incomplete

website address. In most, we see the characters Zhu Wei, cut in half

vertically. These are interspersed with smaller seals, with such legends

as “Eight or Nine Out of Ten” (Shi you ba jiu), “Zhu Wei

Authentication Seal” (Zhu Wei yin jian), or “www zhuweiartden

com.” There is a small signature on the right edge in a variant

of seal script.

The series title reminds that it is spring and these floating figures

may be falling in love. It is the traditional motif of the thickly

blossoming peace blossoms that confirms the romantic connection. The

poet Tao Qian (365-427) gave peach blossoms a measure of fame when he

wrote the “Peach Blossom Spring Preface” about a remote valley far

from the strife of a war-torn world. In later centuries peach blossoms

were increasingly associated with sensual pleasure such as in the

popular seventeenth century play Peach Blossom Fan.[1] In

Vernal Equinox No. 1, while peach blossoms communicate romance, the

individual experience is inequitable. Some figures float in contentment;

earth-bound figures are left merely to think about love, to dwell on

memories or longings. The “Vernal Equinox” series will many more

images. When it is complete, we will have a better idea of how these

individual stories are resolved. |

|

|

|

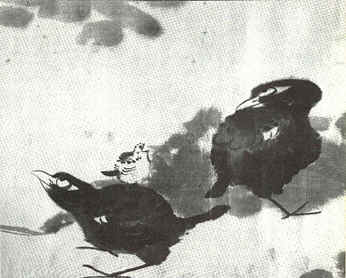

Fig.2

|

Like many of Zhu Wei’s works in recent years, the “Vernal Equinox”

paintings are patinated and the colors made more nuanced by rinsing and

further working the painting surface. How does Zhu Wei achieve this

distinctive effect? Early in his painting career, Zhu Wei elected to

work in the traditional media of soft-haired brush, ink and paper. He,

however, manipulates them in unconventional ways. The mulberry-bark

paper, which is made in Anhui province to his specifications, has to be

strong and resilient to hold up under the repeated soakings. He antiques

the paper by brushing on a mustard-colored wash. The paper being treated

lies on a wooden grid or nubby carpet which creates interesting patterns

as pigments puddle in the hollows of indentations. Zhu Wei keeps watch

as the paper dries, sometimes soaking up or washing off unwanted

pigments. |

|

He

carefully considers the elements that will best express his thoughts,

distilling designs from multiple sketches. For the key persona model

sketches (fenben 粉本)

are made. The model sketch allows him to shift the figures around, to

multiply them (the characters often appear in pairs), and to recombine

them in different contexts. With the main elements in place, lines are

inked with a traditional brush. In the modern era, because Chinese

characters are written with pens, pencils and computers, the soft brush

is no longer a necessity of daily life, but a aesthetic exercise. Zhu

Wei inks such lines as are needed with a deft and light touch. The forms

are primarily formed with color washes in both vivid and muted tones.

Before finalizing the eyes and hair, he rinses the paper under the tap,

crunching the painting here and there. It is a process that takes

finesse, experience and a little courage because, more than once, the

paper has given way, spoiling the painting. Despite the risk, it seems

worth doing as the results are intriguing: an antiqued surface, mottled

and cracked, with a distinctive texture and depth. The relatively slow

pace at which he produces art, recalls the Tang dynasty poet Du Fu’s

description of a contemporary who simply could not be rushed: “Ten

days to paint a pine tree, five days to paint a rock.”[2]

This observation could equally apply to Zhu Wei’s preparation of

materials and compositions.

Enhancing the connection with dynastic Chinese painting are the seals

mentioned above and Zhu Wei’s calligraphy. He inscribes and signs his

paintings in a distinctive hand that is inspired by the clerical script

(li shu) of the third to first centuries BCE. When the inscriptions are

written in white on vertical black panels, they form strong graphic

elements in the composition and resemble the calligraphy on

archaeologically-excavated wooden or bamboo slips. At other times the

vertical rows seem to float like propaganda slogans that, during Zhu

Wei’s youth, hung from balloons at major gatherings.[3]

Zhu Wei’s art has been shaped by the unique circumstances of his age

and life experience. Growing up in an army household, Zhu Wei was an

impetuous youth with little inclination to do his parents’ bidding. In

1982 at age sixteen he enlisted in the People’s Liberation Army. At

the time, the status of the army was in momentary decline. During the

Great Proletariat Cultural Revolution, the PLA had enjoyed high position

due to its having preserved China from devolving into a full-fledged

civil war in 1967-1968. As the only government organization reliably

loyal to the Central Government, the PLA had restored order after the

chaos unleashed by the Red Guards. From the summer of 1968, the PLA was

directing the Cultural Revolution with Mao’s wife Jiang Qing serving

as the PLA’s cultural impresario. The arrest in 1976 of Jiang Qing and

the Gang of Four (characters who would later appear in his paintings)

and their conviction in 1981 tarnished the military’s heroic

reputation. The momentous redirection of government policy to economic

reform and engagement with the outside world further diminished the role

of the army. Because his father was a soldier, Zhu Wei was aware of this

shift in perception, but, given his interest in art, enlisting in the

army trumped the alternative of following his mother into medicine.

|

|

After three years as a regular enlistee, Zhu was admitted to the PLA Art

Academy in the Haidian district of Beijing, and his enthusiasm for all

things visual was put to the test. The training was both rigorous and

tedious. One exercise was to practice drawing lines and circles with a

rolled up paper tube. The tip of the tube had to be inked just so. The

arm had to be suspended above the paper; leaning an elbow on the table

resulted in an uneven line. Too much pressure and the hollow tube would

crunch and bend. Hours of drawing lines and circles with a squishy paper

tube drove some young minds to distraction. If one lasted, then the

discipline took hold and eventually provided precision, deftness of

touch, patience, and a sense of pride. |

Fig.

3 |

|

The

study of approved literature and political thought provided another

strand for Zhu Wei’s art: the poetry of Mao Zedong (1893-1976), and

the recitation of official slogans such as Art must serve the people,

The past should serve the present, Hold high the great red banner,

Implement the Four Modernizations. At the same time, the restrictive

atmosphere of the military encouraged day-dreaming and the creation of

an imaginative world. Because of his decade-long association with the

PLA, when he began painting, soldiers and officials frequently appear in

his works as well as the mind-numbing tedium of meetings. Graduating

from the Art Academy in 1989, Zhu drew an assignment that was not to his

liking, so he turned to what would become a second major influence in

his art, film.

In 1990 he enrolled in the Beijing Film Academy for three years and

began to assemble in memory hundreds of classic films. At the end of

1992, in anticipation of completing the course and having to make a

living, Zhu Wei began to think about painting as a career. For what he

had to say, painting was the language with which he was most competent.

The art of film making, however, gave him a unique perspective. The

framing of many paintings resonates with a film shot or a full-screen

close up; some compositions bear a resemblance to story boards, or to

movie sets. More importantly, film informed the way that Zhu thought

about painting as narration. He conceived of his paintings in terms of

allegory and story telling. In any given series, the paintings

communicate with each other like scenes in a film or like a succession

of frames. However striking they are individually, the paintings are

more revealing in aggregate. They are less like a traditional narrative

handscroll, or a series of album leaves, and closer in mood to a

sequence of film clips.

Popular culture contributed further contemporary influences. Elements

from novels, plays and rock music appear in his paintings. Zhu Wei was

captivated by the immediacy of rock music. Cui Jian, one of the key

figures of China’s new music scene, wrote lyrics that became Zhu

Wei’s text, providing inspiration for images and inscriptions. In the

regular patterning of bars and bold ink dots in the series “Descended

from the Red Flag” or “Story of sister Zhao,” one can sense the

insistent beat of rock music.

|

|

Fig.

4 |

|

|

CLASSICAL

ALLUSIONS and ILLUSIONS

When Zhu Wei considers pictures of China’s rich visual past, he

gravitates to the art of the imperial painting academies, especially the

idealized realism of Song dynasty painting. His incorporation of

traditional motifs from court works, however, does not mean that Zhu Wei

could have won a position in an imperial painting academy. In dynastic

China, serving as a court artist required not only technical facility,

but also a certain disposition, a willingness to paint whatever the

court required. Under emperor Huizong (r. 1100-1125) rigorous

examinations were instituted to select painters. In skill and

imagination, Zhu Wei would have passed with ease. More difficult would

have been the requirement to conform to a style specified by the court.

As one mid-twelfth century author wrote:

What was esteemed at that time was formal likeness alone. If anyone had

personal attainments and could not avoid being expressive or free, then

it would be said that he was not in accordance with the rules or that he

did not continue the heritage of a master.[4]

One suspects that Zhu Wei would not have made the cut, for although he

paints with the precision and meticulous techniques of an academy

painter, his style is uniquely his own. Zhu Wei is gifted and

disciplined but also opinionated. During the reign of Emperor

Huizong’s father Shenzong (r. 1068-1085) artists were recommended to

the court rather than selected by examination and his father was more

tolerant. After Emperor Shenzong ascended the throne, a famous painter

named Cui Bai (active second half 11th c.) was summoned to court at the

beginning of the Xining reign (1068-1077). Biographies relate that

although Cui Bai was an exceptional painter, he was said to be overly

casual and unable to fulfill his responsibilities. By circumstance and

inclination, Zhu Wei has a bit of the independent personality of a Cui

Bai.

While Song dynasty court painting has the greatest drawing power for Zhu

Wei, his taste is admirably eclectics. He reveres Fan Kuan’s

monumental landscape of about 1000 CE, Traveling among Streams and

Mountains (hanging scroll, Taipei Palace Museum) with its breathtaking

scale. He esteems the court paintings of the twelfth and thirteenth

centuries, such as Water Studies by the court painter Ma Yuan (active

ca. 1190-1230, handscroll, Beijing Palace Museum) and the Flower Basket

by Li Song (active ca. 1190-1230) with its precise brushwork and

balanced use of strong colors (Fig.

3).

Zhu Wei is a particular fan of the work of the early Qing dynasty

(1644-1911) individualists Zhu Da (Bada Shanren, 1626-1705) and Shitao

(1642-1707), both of whom were descendents of the Ming dynasty imperial

clan. Their idiosyncratic works defined life-long struggles to create

identity and find acceptance under Manchu rule. In the dangerous world

of the early Qing dynasty, when Ming loyalist generals were still

battling Manchu forces, both Bada Shanren and Shitao hid their imperial

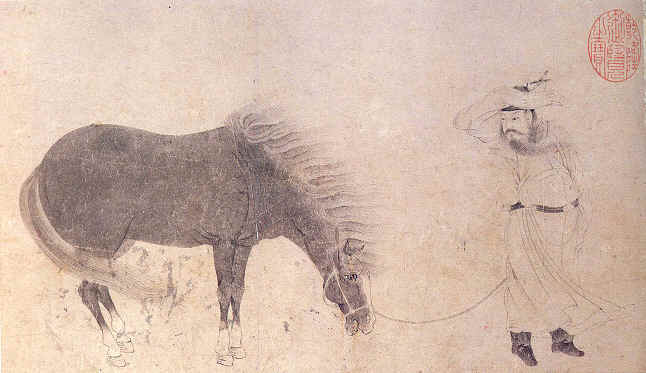

lineage and were guarded in making friends. Bada’s paintings of birds

and fish show a keen awareness of the dangers lurking in relationships.

His birds anxiously eye each other, alert to hidden agendas (Fig.

4).

This sense of caution informs the cast of characters that people Zhu

Wei’s paintings and, beyond body language, it is the eyes that

communicate emotions. While some appear self-satisfied or tolerant, many

are watchful, wary, and still others are resigned, bitter, or

vindictive. They all seem to be negotiating their way through social

mine fields, careful not to misstep. The series of paintings of children

performing on a tightrope is evocative of the paranoia that typified the

aftermath of the era of class struggle in 1990s China. The children have

the anxious expressions of kids who are accustomed to being punished but

are not sure why. Earnestly concentrating on finding the right balance,

they strive to please with a good performance.

|

|

Fig.5 |

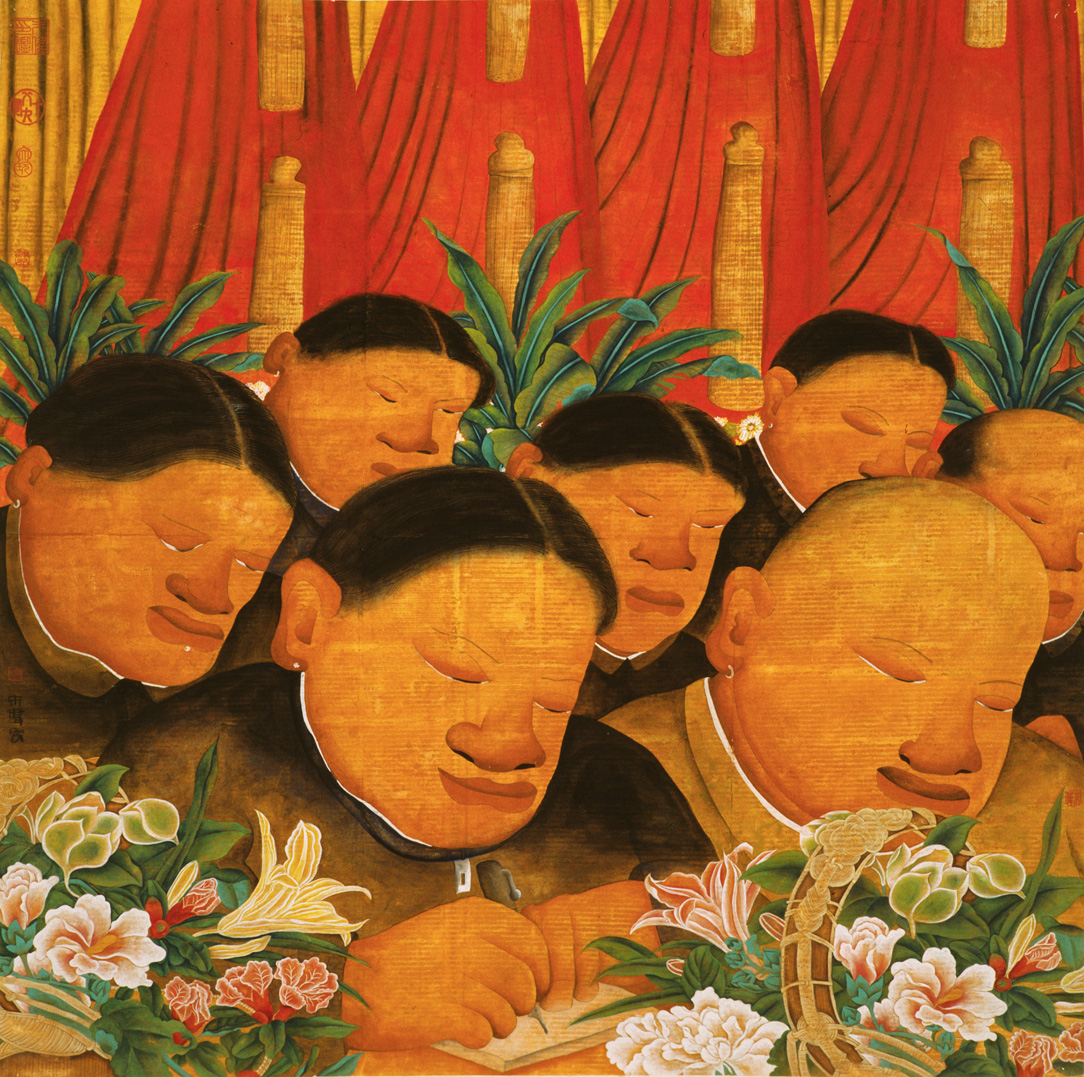

His well-known series titled “Utopia” features huge heads on sturdy

bodies participating in official meetings. In a sequence of as many as

fifty paintings, party members listen with respect, with boredom,

sometimes dutifully taking notes with stubby fountain pens. Because Zhu

Wei has sat through many of these meetings, his portrayals are

sympathetic for he knows what it is to struggle to keep attention. Small

details are entertaining: a People’s Representative has an ear stud

suggesting punk leanings; a large worm hole in a robust banana plant

hints that it is past its prime. The meetings feature huge red flags and

a cheerful floral display of the sort that graces the dais at every

formal gathering (Fig.

5). |

|

The

basket of flowers adapted from the Li Song album leaf of figure four

fits well as an emblem of the modern court. The vivid fresh flowers form

a contrast with the grizzled, vacuous, or attentive faces listening to

the drone of speeches that will reveal the new party line.

Juxtaposition of polychrome realism and artful criticism is not new to

the twentieth century. In Chinese painting history, although the

writing brush was the implement of choice for scholars wishing to hint

at discontent, vivid color was also employed to lodge silent complaints,

especially in vegetable and flower paintings.[5]

Here “realism” does not mean fidelity to the phenomenological world

but rather to psychological reality, the truth that is found in Zen

Buddhist and literati monochrome ink painting.

Mixing ancient and modern elements often results in humorous and ironic

pictures. In The Trials of a Long Journey No. 2 of 1994, for example,

there is a visual quotation from the twelfth century handscroll The

Night Revels of Han Xizai (Beijing Palace Museum, attributed to Gu

Hongzhong of the tenth century). The Night Revels was said to have been

commissioned to record the rakish Minister Han Xizai’s evening

soirees. In the Song dynasty handscroll, the women provide the

full-range of entertainment from music and dance to sexual favors. In

the background of Zhu Wei’s painting, one sees a pair of figures from

The Night Revels composition: a man with his arm around the shoulder of

a young girl urges her off to a tryst. The irony (and irreverence) of

Zhu Wei’s work comes from the series title, “The Trials of a Long

Journey,” or in Chinese “a thousand mountains, ten thousand

rivers,” a reference to the Long March.[6]

|

|

Another traditional source tapped by Zhu Wei is the lore of the horse.

In dynastic Chinese literature and painting, horses were frequent

metaphors for human talent in all its variety. The noble stallion, the

lazy mount, the abused steed, the starving nag all appear in literary

allegories and paintings. Horses are depicted responding to their riders

in the excitement of the hunt, interacting with their handlers, enjoying

or enduring the existence that it is their lot. The intelligence and

awareness of such horses, is captured in a well-known wall painting in

the tomb of Lou Rui, the prince of Dongan of the Northern Qi (550-575).

Among the equestriennes parading on the walls, a few steeds startle us

as they look askance or directly out at the viewer.[7]

The wall painter seems to tell us that these hard-working horses know

that they are metaphors. |

Fig.

6 |

|

Why are horses wandering through Zhu Wei’s paintings? Often upstaged

by foreground heads that partly obscure them, the horses seems to have

personal meanings. One source that he has used multiple times is a horse

and groom painting that is attributed to the great scholar, painter, and

calligrapher Zhao Mengfu (1254-1322). In Training the Horse (Fig.

6),

the groom stands in the conventional position to the right of the

horses’ head. What is unconventional is the stiff wind that whips the

horse’s tail and mane as well as the groom’s sleeves, robe, and

whiskers making the title of the painting ironic. How can one train a

horse in a gale-force wind that swallows up all sound? Zhu Wei links the

image to the military life that he had known for ten years. As in other

series, he experimented with the horse and groom, rearranging them,

juxtaposing them with other figures. In Racing Horse on a Rainy Night,

No. 3, the groom is replaced by a soldier who sits on the ground with a

cloth-wrapped bundle of simple victuals next to him (Fig.

7).

In the pinched expression on his face we can feel the wind’s cold

bite. In another version, Racing Horse on a Rainy Night, No. 5 (1998),

the “groom” is a female cadre with her head wrapped in scarf, while

the horse’s long tail is blown around her shoulder (Fig.

8).

Because Zhu Wei was born in the year of the horse (in the Chinese

vernacular, he belongs to horse, is a horse), we cannot discount the

possibility that some of these steeds represent the artist himself. This

connection is made more likely in Racing Horse on a Rainy Night, No. 5

where the otherwise rarely-seen sprigs of bamboo (zhu 竹)

makes a homophonic pun on the artist’s surname. Again, ancient and

recent past are deployed to serve the present.

|

|

Fig.7 |

|

|

WEIGHT

and WEIGHTLESSNESS

The poet Tao Yuanming, who was cited above as the author of Peach

Blossom Spring preface, had a lack of patience for the pomposity of rank

and class airs. Tao had the talent to serve in a government position and

took a post at his wife’s insistent urging. Less than three months

into his service, Tao was told that, to receive a visiting official of

higher rank, he had to don a particular robe and belt as a sign of

respect. To Tao, the arbitrary distinction was cause for resignation

just eighty days after taking office. The event made him realize that

rural poverty was preferable to the onerous - if well compensated -

protocol of bureaucracy. Zhu Wei can identify with this attitude.

Although not trained as a sculptor, Zhu Wei has been inspired by

difficulties of expression in his two-dimensional art to create witty

and stylish three-dimensional paintings. (If China can have “silent

poetry,” then it should be possible to have “three-dimensional

painting.”) Zhu Wei’s monumental bronze figures of Party cadres lean

forward about to tip over. Their bulky physicality expresses things that

could not be easily conveyed on paper. First created in 1999 at the time

of the fiftieth anniversary of the People’s Republic of China, the

pair of enormous figures in politically-correct Mao jackets stand at

attention with shoulders back, arms at their sides, heads raised. They

are rooted to the ground even as they eagerly press forward 往前进.

The solidity bespeaks unflinching confidence; the uplifted heads suggest

respect for higher authority, while the absence of eyes suggests blind,

unthinking obedience.

|

|

The surface is the most fragile aspect of the sculptures, and a telling

feature. The bronze (or in some cases, painted fiberglass) figures have

a dusty encrustation created with sandy mud from the banks of the

Yangtze River. They look like freshly-excavated objects: they resemble

artifacts to be housed in a museum and studied as historical relics as

part of China’s cultural heritage. When a pair was shown in the atrium

of the IBM Building in New York, the installers did not understand that

the patination was part of the sculpture and scrubbed them clean. The

earthen patination situates these sculptures with tomb figurines as

examples of the ideal servant in the afterlife - silent, loyal,

sycophantic. This cynical interpretation does not credit the reality

that the CCP has many hardworking members who actively contribute to

society. cadres are a weighty presence and wield great power. Like these

immobile bronze behemoths, they are impossible to dismiss. |

Fig.8 |

|

Zhu Wei’s creation of art is an unusual amalgam of past and present.

Visually, his paintings are more easily associated with the professional

class of painters in dynastic China and yet the messages of empathy and

social criticism are very clearly in the tradition of the educated

elite. His awareness of the weight that words and images have carried in

both traditional and modern China make his art both fascinating and

obscure: messages are deeply imbedded in layered allusions and small

details. As he enters his forties, Zhu Wei continues his keen

observations of self and society, interested in a broad range of

cultural issues. His commentaries are tempered with humor, the edginess

is softened with humanity. In the best tradition of Chinese expressive

art, Zhu Wei’s paintings record quickly changing social norms, human

foibles, and political absurdities, in short, the life that he is

witnessing and the history that is unfolding before us.

FIGURES

1.

Zhu Wei, “Vernal Equinox No. 3,” ink and color on paper, 121 x 143

cm.

2.

Anonymous, Song dynasty, Peach Blossoms, round fan, ink and color on

silk, 24.8 x 27 cm. Beijing Palace Museum. From Nie Chongzheng ed.,

Gugong bowuyuan cang wenwu zhenpin daxi: Jin Tang liang Song

huihua: huaniao zoujin (Shanghai: Kexue jishu, 2004), pl. 49.

佚名《碧涛图》

3.

Zhu Da (1626-1705), Lotus and Birds, ca. 1690, detail, handscroll, ink

on satin, 27.3 x 205.1 cm. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York,

Bequest of John M. Crawford, Jr. 1988. 朱耷《莲池禽鸟图》

4.

Li Song (active ca. 1190-1230), Flower Basket, album leaf, ink and

colors on silk, 19.1 x 26.5 cm. Beijing Palace Museum. 李嵩《花篮图》

5.

Zhu Wei, Utopia No. 46, 2005, ink and color on paper, 120 x 120 cm.

朱伟《乌?邦四十六号》

6. Zhao

Mengfu (1254-1322), Training a Horse, album leaf, ink on paper, 22.7 x

49 cm. Taipei Palace Museum. From National Palace Museum, Hua ma ming

pin tezhan tulu (Taipei: National Palace Museum, 1990), p. 33. 赵孟?《调良图》

7.

Zhu Wei, Racing Horse on a Rainy Night, No. 3, ink and color on paper,

1997, 66 x 66 cm, Private Collection. From Zhu Wei’s Diary (Hong Kong,

Plum Blossoms Ltd, 2000), p. 214.

8.

Zhu Wei, Racing Horse on a Rainy Night, No. 5, ink and color on paper,

1998, 131 x 131 cm, Private Collection. From Zhu Wei’s Diary (Hong

Kong, Plum Blossoms Ltd, 2000), p. 216.

NOTES

[1] Tao Yuanming (365-427), “The Peach Blossom Spring,” James

Robert Hightower, translated and annotated, The Poetry of T’ao

Ch’ien (Oxford: Clarendon, 1970), pp. 254-256. Kong Shangren (),

The Peach Blossom Fan, trans. Chen Shih-hsiang and Harold Acton, The

Peach Blossom Fan by K’ung Shang-jen (Berkeley and Los Angeles:

Univ. of California, 1976).

[2]

Zhu Jingxuan (active mid 9th c.), Tang chao minghua lu (early

840s), quoting Du Fu’s (712-770) appraisal of the painter

Wang Zai. 朱景玄《唐朝名画录》妙品上八人,

杜甫对王宰的评价:“十日画一松,五日画一石”.

[3]

For example see Plum Blossoms Ltd., Zhu Wei Diary (Hong Kong: Plum

Blossoms International, 2000), New Positions in the Brocade Battle,

no. 3, p. 79, Box No. 3, p. 274.

[4]

Deng Chun, Hua ji, juan 10邓椿《画继》卷十:

盖一时所尚,专以形似,苟有自得,不免放逸,则谓不合法度,或无师承。

[5] Alfreda Murck, "Paintings of Stem Lettuce, Cabbage, and Weeds:

Allusions to Tu Fu's Garden", Archives of Asian Art (亚洲艺术档案)

48 (1995), 32-47. 中译:

姜斐德《以莴苣、白菜和野草为画——杜甫菜园的隐喻》《清华美术》,

2005-12.

[6]

《万水千山二号》,

Plum Blossoms Ltd., Zhu Wei Diary (Hong Kong: Plum Blossoms

International, 2000), p. 47.

[7]

Lou Rui tomb wall painting, detail, Northern Qi (), Shanxi Province

Cultural Heritage Research Institute. From Bei Qi Dongan wang Lou

Rui mu 《北齐东安王娄睿墓》

(北京:文物出版社,2006),

color plate 32.

First published in ZHU WEI'S ALBUM OF INK PAINTINGS 1998-2008, p.26-36, published by Plum Blossoms (International) Ltd., Hong Kong, 2008

Reprinted in Oriental Art . Master, December 2011, p.92-97

Alfreda

Murck earned a PhD at Princeton University in Chinese art and

archaeology with an emphasis on the history of Chinese painting. She

worked in the Asian Art Department at the Metropolitan Museum of Art,

New York, from 1979-1991. Since 1991 she has lived with her husband

Christian Murck in Taipei and Beijing. She has published articles on

Chinese art and a book on how eleventh century scholars used poetry in

painting to express dissent: Poetry and Painting in Song China: The

Subtle Art of Dissent (Harvard University Asia Center, 2000). She

is a lecturer at the Central Academy of Fine Arts, and is a researcher

in the Palace Museum’s Painting and Calligraphy Research Center and a

consultant to the Palace Museum’s English web-page. |

|

古为今用

——朱伟作品中的传统元素

姜斐德

朱伟之所以著名,在于他经常使用源自中国传统绘画的题材来表现政治和社会的主题。他把古代人物和毫无疑义的现代人物的形象进行融合,以反映自改革开放伊始的八十年代初以来的中国社会与生活。朱伟也使用传统的媒介,但他独辟蹊径而自成一体。朱伟的作品和文革有着清晰的联系,同时,他也糅和了帝制中国的艺术形式,以此来叙述发生在最近的故事,笔调有种温和的讽刺意味。身着中山装的干部与宋元的题材一同粉墨登场,似乎它们同为久远历史的一部分。朱伟的艺术反映了翻天覆地变化中的文化与社会,于是我们要问:在中国文化中,什么是持久不变的?如何理解1949年以来的历史?

朱伟最近的作品系列名为《开春图》,这一系列显示了他新的创作方向。《开春图三号》(图1)画的是飘浮在花叶中处于失重状态的人,背景留白。人物似乎面无表情,但又各自有不同意蕴,有的显得阴郁、无动于衷,有的忧伤,有的惊诧,有的则志得意满。他们的手插在衣兜里或藏在袖子里,不禁让人想到“袖手旁观”这个成语。人物形体大小各异,但无定规,不足以说明前后次序或空间感。他们头发炸开,似乎他们正在往下坠落,或者说像微风中随风飘荡的种子,更像是没有拴线的气球。他们彼此没有关联,既不互相瞧着,也不望向我们。画的左下角,一束桃花正灼灼开放,比所有人都大,支撑住了整个画面。此桃花来自南宋(1127-1278)一位匿名画家的小团扇画,然而在朱伟笔下变得更为硕大,并且是画在纸上而不是绢上(图2)。画面左右边界处均有巨大的印章,如藏家收藏章一般,半钤在画上半消失于绫子边缘。其中的一个印章是“www”,一个未完成的网址;在画面的大部分,我们可以看到“朱伟”二字,被垂直地切去了一半。此外,画面上还点缀着其它较小的图章,如“十有八九”、“朱伟印鉴”、“www.zhuweiartden.com”等。画面上有小的画家签名,字体略近魏碑或金农的漆书。

这个系列令人想起这是春天,漂浮的人们或许正坠入爱河。繁盛绽放的桃花是传统绘画的题材,让人产生烂漫的遐想。诗人陶渊明(365-427)在《桃花源记》中,描写了远离战乱世界的遥远山谷桃花源,这使得“桃花”闻名遐尔。而接下来的数个世纪,“桃花”逐渐与感官上的愉悦联系起来,比如在十七世纪广为流传的戏剧《桃花扇》里[1]。在朱伟的《开春图一号》里,桃花依旧传达出浪漫意味,可个人的体验却大相迥异。漂浮着的一些人心满意足;脱离了大地的人们只能去思考爱,只能去琢磨回忆与渴望。《开春图》这个题目可能会让一些中国人联想到著名歌手董文华的歌曲《1992年,又是一个春天》,这首歌写于邓小平南巡,重新推进改革开放之后。《开春图》这个系列还在延续中,只有在其完成时,我们才能明了这些个人的故事将如何终结。

如朱伟近年来的许多作品一样,《开春图》呈现出古色古香的面貌,对画作表面的水洗以及进一步处理使颜色褪变得更为微妙。他是如何做出这极具个人特色的效果的?在绘画生涯早期,朱伟就选择了以毛笔、墨、纸张等传统媒材来创作,然而,他用非传统的方式使用它们。安徽订制的桑树皮纸必须质地牢固有弹性,经得起反复浸润,因为纸张必须刷上棕黄色颜料来做旧。刷的时候纸张下面垫上有栅格的木板或糙面的地毯,当颜料在凹处沉淀凝结时,纸上便现出有趣的图案。纸张干燥过程中,朱伟一直在旁守候,不时吸掉或洗掉不想要的颜料。他审慎考虑所有最能表达他想法的元素,从多达数倍的草稿图中提炼出构思。主要的人物角色都有粉本,用粉本的好处是,角色能被挪动、复制(人物通常成对出现)、在不同的背景中组合。主要元素到位后,线条画需用传统毛笔渲染。在如今这个时代,写出中国字的是钢笔、铅笔和电脑,柔软的毛笔不再是日常生活必需品,而演化为一种美学活动。渲染线条画时,朱伟的笔触必须灵动轻柔,这样,事先做旧的图画就同时具备了鲜活与灰暗的质地。在最后完成眼睛和头发之前,他把画纸放到水龙头下冲洗,揉搓画作的某些部位。这一步骤极需细心、经验和一些勇气,因为不止一次纸张曾被揉碎,整张画于是便被毁损。尽管存在风险,这一步还是值得的,原因就是那及其迷人的最终效果:古董般斑驳皲裂的表面,别具一格的皴纹和深度。出于同样的原因,他创作的步调也相当缓慢,令人回想起唐代诗人杜甫的诗句:“十日画一松,五日画一石”[2]。这句诗同样也能用于朱伟对材料和构图的准备。

朱伟的书法与上文中提到的印章也加强了其画作同中国古代绘画之间的联系。他在画作上的落款和字体非常独特,灵感来源于公元前三世纪到公元前一世纪的隶书。白色的款识写在竖直黑底色块上,形成强烈的构图效果,类似于考古挖掘出来的木牍或竹简。另外一些时候,竖直的字行犹如漂浮半空的宣传标语,正如朱伟年少时从集会人群头顶的气球垂下的标语一样。[3]

在独特环境中成长与生活的经历塑造了朱伟的艺术。他出身于军人家庭,在躁动的青年时代,他极少听从父母的命令。1982年,十六岁的朱伟应募加入中国人民解放军。那时军队的地位大幅下降。在伟大的无产阶级文化大革命期间,因为在1967-1968年间阻止中国陷入全面内战,中国人民解放军的地位极其崇高。作为中央政府信任的唯一一个官方机构,中国人民解放军收拾了红卫兵留下的烂摊子,恢复了原有秩序。从1968年夏开始,毛泽东的妻子江青成为中国人民解放军文化掌权者,其后中国人民解放军开始指挥文化大革命。1976年江青和四人帮(这些人物以后将出现在他的作品中)被捕,1981年被宣判有罪,自此以后,军队的辉煌声誉便失去光泽。当政府政策出现了重大转向后,改革开放进一步削弱了军队的重要性。由于父亲是一名军人,朱伟对这一转变有深刻认知,然而,对爱好艺术的朱伟而言,应征入伍总胜于步母亲的后尘进入医药界。

服役三年之后,朱伟被位于北京海淀区的解放军艺术学院招收入学,从这个时刻开始,他对所有视觉事物的热情将接受检验。学校训练既严苛又乏味。其中一项训练是用尖端蘸上墨水的纸卷画直线和圆圈,手臂必须悬浮在纸上方,手肘稍稍碰一下桌面就有可能画出不匀称的线条。下笔稍重,空心的纸卷就可能被压扁或压弯。用软绵绵的纸管接连画上数个小时的直线和圆圈,要不让年轻人分心非常艰难,可一旦坚持下来,就会掌握住规则,最终收获的将是精细灵动的笔触、耐心、以及自豪感。对官方文学和政治思想的学习是造就朱伟艺术的另一条线:毛泽东(1893-1976)诗词,朗读宣传官方口号如“文艺为人民服务”、“古为今用”、“高举红旗”、“实现四个现代化”。同时,军队里的严厉氛围却引起了白日梦,创造一个幻想世界。当朱伟刚刚开始作画时,数十年与军队的关联使他笔下常常出现军人和官员的形象,时常出现的还有那些令人头昏脑胀的沉闷会议。1989年,朱伟从解放军艺术学院毕业,那年他被指派画他并不所喜好的东西,于是,他转向了第二个将对他的艺术具有重大影响的领域——电影。

1990年,朱伟被北京电影学院录取,数以百计的经典影片伴随了他三年的学习生涯。1992年末,预计将完成学业去谋生,朱伟开始考虑将绘画作为终生职业。事实上他不得不承认,绘画是他最擅长的语言,而拍电影给他提供了独特的视角。许多朱伟画作的取景让人联想起电影摄影或一个封闭的全屏幕;有些构图则与故事板类似,或像是电影场景。更为重要的是,电影提供了朱伟把绘画用作叙述的方法。他把绘画当成寓言和故事来讲述,和电影中的连续场景或连续数帧画面类似。在他的任何绘画系列里,前后都有关联,不论每张画多么自成一体,作为一个系列它们还是会透露出更多信息。不同于传统的故事手卷抑或是册页,朱伟的系列作品在状态上更接近于电影剪辑。

流行文化则带来了更多当代气息。朱伟的画作中出现了从小说、戏剧、音乐中汲取的素材,摇滚乐的震撼使他着迷。崔健是中国新音乐中不可或缺的关键人物之一,他写的歌词成为朱伟的文本,使他获得图像与款识的灵感。看到《红旗下的蛋》和《赵姐的故事》系列中他一贯的栅格图案配上大胆的墨点,人们确乎能感受到摇滚乐的持续冲击。

古典暗喻及幻像

当朱伟面对中国过去丰饶的视觉艺术时,他倾心的是来自宫廷画院的艺术,尤其宋代理想的写实主义绘画。朱伟善用宫廷书画的传统题材,但是,这不表明他能够在宫廷画院里谋得一席之地。帝制中国的宫廷画家不仅具备技艺上的能力,还得拥有某种职务,朝廷要什么就得画什么。宋徽宗(1100-1125年在位)曾亲自严格挑选任命每一位画家。就技法和想象力而言,朱伟当然能毫不费力地通过甄选,困难之处在于遵照朝廷要求的风格做画。诚如一位十二世纪中叶的邓椿所述:

盖一时所尚,专以形似,苟有自得,不免放逸,则谓不合法度,或无师承。[4]

朱伟使用画院画家的工笔技法作画,这并不能成为怀疑他无法突破传统束缚的理由,实际上他的风格仅仅属于他自己。朱伟有才华,受过良好训练,但也非常有自己的想法。在宋徽宗的父亲神宗(1068-1085年在位)统治期间,画院画家的甄选方式是举荐而非考取,神宗的父亲对此则更为宽松。神宗登基后,著名画家崔白(活跃于11世纪后半叶)于熙宁年间(1068-1077)应召进入画院。据传记记载,崔白画艺超群,却生性疏阔,乃至无法完成他在画院的职责。无论从环境还是个性上来看,朱伟都多少有些崔白的独立个性。

尽管宋朝画院绘画对朱伟有强烈影响,他的趣味并不拘泥于此。他将范宽那幅创作于公元十一世纪的经典《溪山行旅图》(手卷,台北故宫博物院藏)改成了尺寸惊人的新作。他看重十二、

三世纪的宫廷画作,因为它们有细密的笔法和富丽的色彩(图3),譬如宫廷画家马远的《水图》(手卷,北京故宫博物院藏,马远活跃于1190~1230年)和李嵩(活跃于1190~1230年)的《花篮图》。朱伟尤其欣赏明末清初的个人主义者朱耷(八大山人,1626-1705)和石涛(1642-1707),这两人均为明皇室的后裔。二人奇僻的画风勾勒出他们长达一生的挣扎——那是在满洲统治下不断确认自我、寻求认同的挣扎。清朝前期,社会动荡,明朝遗老遗少仍处在与满清的斗争中,八大山人和石涛不得不隐藏他们的皇族血统,甚至连交友都受监视。八大笔下的鸟和鱼总显示出对周遭环境的敏锐知觉。他的鸟儿紧张地注视彼此,警觉地隐藏起他们的动机(图4)。这种谨小慎微让人想起朱伟笔下的人物,那些人物不是用身体语言,而是他们的眼睛暴露出了他们的感情。尽管这些人中的一些看起来踌躇满志,或是顺从忍耐,有些人则警觉而机敏,但是,其它人还是得听天由命、愁眉苦脸、怨气冲冲。他们似乎都在社会这个地雷阵里踽踽前行,生怕走错一步。《孩子走钢丝》这一系列作品很容易将我们带回到阶级斗争之后的九十年代,这些孩子们面上挂着习惯了被莫名惩罚时才有的神情,他们正全神贯注于找到钢丝上的平衡,

竭尽全力用尽善尽美的表演来取悦于人。

著名的“乌托邦”系列刻画了那些顶着大脑袋的强健身躯参加官方会议的情景。这一系列有五十幅左右,会议中党员们百无聊赖,但仍貌似恭敬地听着,还时不时用粗短的钢笔忠诚地记录着什么。因为朱伟曾多次忍受这样的会议,所以他的笔触是具有同情心的——他知道要挣扎着保持注意力到底是什么含义。小细节也很有意思:一位人大代表穿了个耳钉,说明他的朋克倾向;在生机勃勃的芭蕉叶上有一个巨大的虫蚀洞,表明它已经渡过了青春期。巨大的红色旗帜和繁花似锦的讲台摆设是这种正式群众聚会场合不可避免的(图5),从李嵩册页里来的花篮则很好地担任了现代宫廷的象征。台上的演讲正宣扬着党的新路线,而台下那些正在倾听着的苍老空虚的面容却与鲜活的花朵并置在一起,形成一个绝佳的对照。

色彩丰富的现实主义与隐蔽的针砭批判在二十世纪已经不是什么新鲜事。中国绘画史上,尽管文人墨客更爱用笔法来暗示他们的不满,然而鲜明的色彩也被采纳于表达沉默的抗议,在植物花草的绘画中尤为如此[5]。在这里,“现实主义”不代表同现实世界保持一致,而是同心理现实保持一致。我们可以在禅宗和文人的单色水墨作品中发现这个事实。

将古代和现代元素融合起来,通常导致的结果是幽默与讽刺。如1994年的《万水千山二号》,在视觉形象上援引了十二世纪的手卷《韩熙载夜宴图》摹本(北京故宫博物院藏,原本为公元十世纪的顾闳中所作)。《夜宴图》据说是顾闳中奉命夜至素有放逸之名的大臣韩熙载家,窥视其夜宴的情景而画的。在这幅宋代摹本中,女性提供了从音乐舞蹈到性挑逗的全套娱乐服务。而在朱伟这幅作品的背景中,人们可以看到与《夜宴图》构图相似的一对人物:一个男人正搂着一个女孩的肩,怂恿她同他去幽会。朱伟的嘲讽(和不恭)来自于这个作品系列的名字——《万水千山》,意指长征。[6]

朱伟接触的另一个传统资源是对马的认知。在中国帝制时期的文学与绘画中,马常常被用来隐喻人在各方面的才华。高贵的种马、慵懒的乘骑、被奴役的战马、饥饿的驽马,无一不出现在文学寓言和绘画里。马的形象是在紧张激烈的狩猎中追随骑手,与骑手合二为一,享受或是忍受它们既定的命运。在著名的北齐东安王娄睿(550-575)的墓室壁画中,马的智慧与洞察力被捕捉得很传神。画中的女仪卫们正列队骑行,而那几匹战马却是人们注意力的中心,它们正白眼斜视或直视着墙外的我们[7]。壁画作者似乎想告诉我们,这些含辛茹苦的马匹完全明了它们自己所代表的寓意。

为何马匹会在朱伟的画作中游荡?前景中鲜明的人物头像常常使马匹藏于暗处,它们似乎有更个人化的涵义。伟大的文学家、画家、书法家赵孟俯笔下的马匹和马夫被朱伟借用过数次。赵的《调良图》(图6)中,马夫按照传统习惯画到了马头的右方,然而画面中却掀起了一阵并非传统的强风,吹得马尾马鬃、马夫的衣袖长袍虬髯,无一不在风中翻飞,结果是使这幅画的名称变得极具讽刺意味。人怎么可能在吞噬一切声响的狂风中驯马?朱伟把这个画面同他熟谙的数十年军旅生涯联系起来,在一些系列作品中,他实验性地将马匹和马夫重新构图,并加入了新面孔。《图夜跑马图三号》里,马夫被一名士兵代替,士兵坐在地上,身旁放着一布包裹的粮食(图7)。从士兵紧锁的愁眉中,我们感受到了寒风的凛冽。在另一幅作品《雨夜跑马图五号》(1998)中,“马夫”又变成了个女干部,围巾包住她的头,长长的马尾扫着她的肩(图8)。朱伟在马年出生(按中国属相算,朱伟属马),我们不能排除这些战马中的几匹有代表艺术家本人的可能性。在《雨夜跑马图五号》中这种联系被加强了,画面里罕见地出现竹叶,而中文中的“竹”与艺术家的姓同音,这是再一次的“古为今用”。

重与失重

上文中提到的《桃花源诗并记》的作者,诗人陶渊明,是个难以忍受等级森严的氛围的人。陶渊明有做官的天分,在妻子的督促下,他接受了官府的任命。上任后不到三个月,一次有人告诉陶渊明,某大官要来视察,为了迎接这名大官,陶渊明应当束带迎之,以示尊敬。这种粗暴的尊卑之分导致陶渊明上任仅八十天后遂授印去职。这次事件让他意识到,俭朴的田园生活胜过官僚制度下——即使有所补偿——的繁文缛节。朱伟的态度也是如此。

虽然没有经过雕塑训练,朱伟还是从他在二维艺术中遭遇的困难获得灵感,创作出诙谐而极具个人特色的三维绘画。(如果中国有“沉默的诗歌”,那么也有可能存在“三维绘画”。)朱伟经典的铜雕塑作品塑造了向前倾斜站立、几近跌倒的党干部。它们那巨大的实体感表达了不容易在纸上表达的东西。第一尊雕塑创作于中国人民共和国成立五十周年的1999年,两个庞大的人身着政治正确的中山装,站姿毕恭毕敬,双肩收紧,双臂贴于身侧,仰着头。他们紧紧扎根于地面,却表达出强烈的向前进的欲望。他们的坚固性表明了无所畏惧的坚强信心;仰起的脑袋暗示着对更高权威的尊敬,而他们眼睛的缺失则暗示着盲目和愚忠。

雕塑的表面是其最脆弱的部分,也是极具特点的部分。铜(在另一版本中为着色的玻璃钢)像表面有一层灰土覆盖物,那是从扬子江岸取来的沙土。它们使得雕塑看上去似乎刚出土:像是作为中国文化遗产一部分被陈列在博物馆里作为历史遗迹来研究的史前古物。雕塑在纽约IBM大厦中庭安装时,安装者不知道这些尘土锈迹是雕塑的一部分,结果把雕塑擦洗得干干净净。尘土锈迹使雕塑具有墓葬雕像的意味。墓葬雕像象征着来世里理想的奴仆——沉默、忠诚、阿谀。对愤世嫉俗的阐释者而言,说中国共产党有许多成员不辞劳苦地积极投身于社会是难以置信的。干部是重量级的群体,手握巨大权力。像这些岿然不动的铜制庞然大物一样,他们不容忽视。

朱伟的艺术创作是过去与现在相融合的非凡合金。视觉上,他的画很容易让人联想到中国帝制时期的职业画家,然而,他的画所透露的社会精英秉承的移情与社会批判的信息也非常清晰。他意识到传统中国和现代中国承载的文字和图像的力量,这让他的艺术既令人着迷又隐密晦涩:讯息被深深地隐藏在多层暗示和微妙的细节里。步入不惑之年,朱伟仍继续他对自我、对社会的敏锐观察。他对广泛的文化问题怀有兴趣,幽默缓和了他的阐释,人性软化了他的锐利。在中国最好的写意传统中,朱伟的绘画记录了正在迅速转变的社会规范、人性的弱点、政治的荒谬,简而言之,他记录了他正在见证的生活,和正在我们面前展开的历史。

图释(见英文版插图)

1. 朱伟,《开春图三号》,水墨设色纸本,121 x 143厘米]

2. 佚名,宋代,《桃花图》,团扇,水墨设色绢本,24.8 x

2厘米,北京故宫博物院藏。摘自《故宫博物院藏文物珍品大系:晋唐两宋绘画·花鸟走兽》(上海科学技术出版社2004年出版),聂崇正编纂,pl.

49,佚名《碧涛图》

3. 朱耷(1626-1705),《莲池禽鸟图》,1690年,详情,卷轴,水墨缎本,27.3 x

205.1厘米。大都会艺术博物馆藏,纽约,小John M. Crawford于1988年遗产捐赠。

4. 李嵩(活跃于公元1190-1230年),《花篮图》,册页,水墨设色绢本,19.1 x 26.5厘米。北京故宫博物院藏。

5. 朱伟,《乌托邦五十号》,2005年,水墨设色纸本,120 x 103厘米

6. 赵孟俯(1254-1322),《调良图》,册页,水墨纸本,22.7 x

49厘米。台北故宫博物院藏。摘自国立故宫博物院《画马名品特展图录》(台北:国立故宫博物院1990年出版),p. 33。

7. 朱伟,《雨夜跑马图三号》,水墨设色纸本,1997年,66 x 66厘米,私人收藏。摘自《朱伟日记》(香港:Plum

Blossoms有限公司2000年出版),p. 214。

8. 朱伟,《雨夜跑马图五号》,水墨设色纸本,1998年,131 x 131厘米,私人收藏。摘自《朱伟日记》(香港:Plum

Blossoms有限公司2000年出版),p. 216。

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

注释

[1] 陶渊明(365-427),《桃花源记》,James Robert Hightower翻译成英文并注释,选自《陶潜诗作》(The

Poetry of T’ao Ch’ien)(牛津:Clarendon出版,1970),pp.

254-256。孔尚任(1648-1718),《桃花扇》,Chen Shih-hsiang与Harold

Acton翻译成英文,选自《孔尚任的桃花扇》(The Peach Blossom Fan by K’ung Shang-jen)(伯克利与洛杉矶:加利福尼亚大学出版,1976)。

[2] 参考朱景玄(约公元9世纪中期)《唐朝名画录》(9世纪40年代前期)妙品上八人, 杜甫对王宰的评价:“十日画一松,五日画一石”.

[3] 例如万玉堂有限公司出版的《朱伟日记》(香港:万玉堂国际公司出版,2000),新编花营锦阵三号,p. 79,盒子三号,p. 274。

[4] 邓椿《画继》卷十,(收入《画史丛书》第一册,255-356页), 273页。

[5] Alfreda Murck, "Paintings of Stem Lettuce, Cabbage, and Weeds:

Allusions to Tu Fu's Garden", Archives of Asian Art (亚洲艺术档案) 48 (1995),

32-47. 中译: 姜斐德《以莴苣、白菜和野草为画——杜甫菜园的隐喻》《清华美术》, 2005-12.

[6] 《万水千山二号》, Plum Blossoms Ltd., Zhu Wei Diary (Hong Kong: Plum

Blossoms International, 2000), 47页.

[7] Lou Rui tomb wall painting, detail, Northern Qi (550-577), Shanxi

Province Cultural Heritage Research Institute.《北齐东安王娄睿墓》

(北京:文物出版社,2006), 32彩色图.

首次刊发于香港Plum Blossoms国际有限公司2008年出版《朱伟水墨册页 1998-2008》,第26-36页

转载于《东方艺术.大家》杂志2011年12月上半月刊,第92-97页

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

姜斐德,普林斯顿大学中国艺术与美学博士,专攻中国绘画史。1979-1991年,任职于纽约大都会艺术博物馆亚洲艺术部,1991年后与丈夫Christian Murck迁居至台北和北京。曾多次发表有关中国艺术的文章,并著述关于十一世纪文人在绘画中以诗表达怨意的书籍《宋代绘画与诗歌:委婉的抱怨方式》(哈佛大学出版社2000年出版)。目前任中央美术学院主讲教师,故宫博物院古代书画研究中心研究员,以及故宫博物院资料信息中心顾问。 |

|

|