|

| |

|

|

|

The

Meaning of Art

Herbert

Read [British]

42

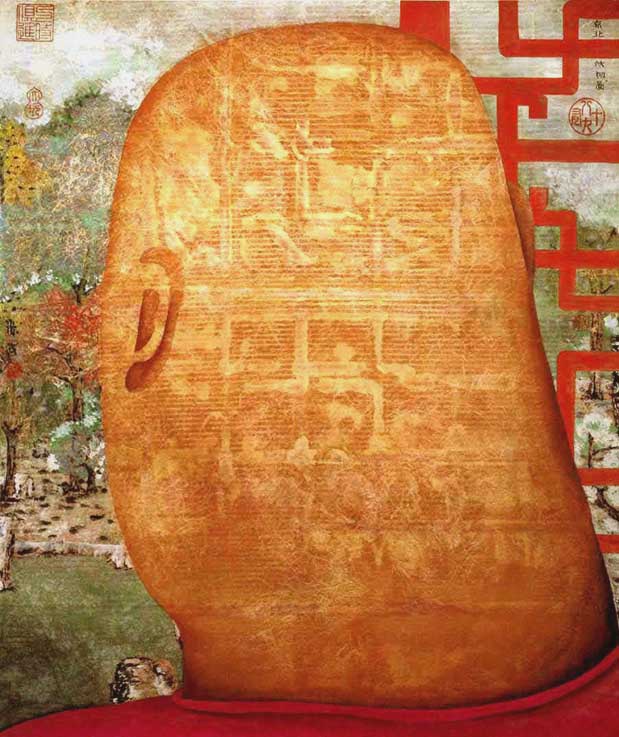

- Chinese art

The

history of Chinese art is more consistent, and even more persistent,

than the art of Egypt. It is, however, something more than national. It

begins about the thirtieth century B.C. and continues, with periods of

darkness and uncertainty, right down to the present century. No other

country in the world can display such a wealth of artistic activity, and

no other country, all things considered, has anything to equal the

highest attainments of this art. It is an art which has its limitations;

for reasons which we will presently consider, it has never cultivated

the grandiose, and has therefore never had an architecture to compare

with Greek or Gothic. But in all other arts, including painting and

sculpture, it achieved, not once but repeatedly, a formal beauty as near

perfection as we can conceive.

|

|

To the average Westerner, the East has always been the land of mystery,

and though modern means of communication and modern methods of

transmitting information, especially the camera and the cinema, are

making him familiar with the external features of Oriental civilization,

its inward spirit still remains strange and remote. When we are

concerned with specifically spiritual things - a religion like

Buddhism or a philosophy like Taoism - we are generally content to

remain outsider, perhaps sympathetic but essentially passive spectators

of way of thought and life which is beyond us. But when we are concerned

with material and objective things like works of art - statues and

paintings, pottery and textiles - we do not have the same humility.

Art, we feel, is an international language, appealing directly to the

senses, and we ought to be able to appreciate Eastern art as easily as

the art of our own civilization. There is a good deal of vague

speculation about the universality of art which encourages this easy

confidence, and from the seventeenth century down to the present time

Oriental art has periodically been a popular craze, and has even

inspired our own artists and craftsman. |

|

|

There can be no doubt, however, that these fashions has been based on a

complete misunderstanding of the art of the East, not only imitating

merely the superficial features of that art, but selecting for imitation

and enthusiasm the worst periods and the worst styles. We are slowly

learning to discriminate more in accord with the best Oriental taste,

and in our museums those ornate and ingenious curios which our fathers

admired are being quietly relegated to the background, or buried in the

cellars, and the authentic art of the East is being acquired and

displayed. But it yields its secret slowly, and one may say that in

order to appreciate these works of art to the full, one has to acquire

new eyes and a new way of looking at the world. For it may be said that,

without exception, the Oriental artist is never looking at the world

from our point of view.

To come near to his point of view, we may approach his art from two

directions. The first, and perhaps the most difficult direction, is that

of technique. European painting, of course, has its technique, and

though it has nothing like the historical consistency of the Chinese

technique, it is a difficult discipline to learn. It involves a

knowledge of the theory of colors, of the mixing of paints, the

preparation of grounds, the difficult effects that a brush can secure

- a complex assembly of practical facts. By comparison with the

Chinese technique is amazingly simple: it involves the knowledge of the

use of one brush and one color—but that brush used with such delicacy

and that color exploited with such subtlety, that only years of arduous

training can produce anything approaching mastery. As is well known, the

Chinese normally write with a brush, and a brush is as familiar to them

as a pen or pencil is to us. The first fact to realize about Chinese

painting is that it is an extension of Chinese handwriting. The whole

quality of beauty, for the Chinese, can inhere in a beautifully written

character. And if a man can write well, it follows that he can paint

well. All Chinese painting of the classical periods is linear, and the

lines which constitute its essential form are judged, appreciated and

enjoyed, as written lines.

|

|

|

Now, just as we affect to judge a person’s character by his

handwriting, the Chinese, with much more science and practice, judge the

quality of an artist by the refinement of his line - its infinite

expressiveness. So much is fairly easy to understand of the art of

painting. But from this art of painting we must proceed to the other

arts - sculpture, pottery, bronzes, lacquer - and in each of them we

shall find a similar technical quality - a quality of infinite

subtlety which reflects the personality of the artist. In pottery, for

example, it is found in the galbe or outline which the pot makes and in

the relation of this outline to the thickness and volume of the pot. As

the clay passes through the potter’s fingers on the revolving wheel,

it is expressing his sensibility as surely and as subtly as the brush

charged with ink expresses the sensibility of the painter. In every work

of art there is the personal signature of the artist - not a vulgar

self-conscious scrawl, but the well-mannered product of centuries of

tradition.

|

|

So much for the technical approach to Chinese art. The other approach

can only be called the metaphysical approach, and what is difficult to

understand and appreciate is the fact that so personal a technique as we

have described has to be combined with a content of extreme

impersonality and abstraction. It is sometimes said that the Chinese

artist attempts to express in his work the harmony of the universe, and

some such cosmic phraseology is necessary to describe his aim. In any

case, that aim has nothing in common with the usual aim of Western art,

which is to represent the particularities of natural appearances. The

Chinese painter will, of course, paint representations of natural

phenomena: he is famous for his landscapes, and they are never merely

the particular landscape and nothing more; behind the particular is the

general -

a

sense sublime

Of

something far more deeply interfused,

Whose

dwelling is the light of setting suns,

And

the round ocean, and the living air,

And

the blue sky, and in the mind of man,

A

motion and a spirit, that impels

All

thinking things, all objects of all thought,

And

rolls through all things.

Those

lines of Wordsworth’s express more nearly than anything in the whole

range of Western culture the spirit of Eastern art. Naturally, that

spirit undergoes transformations during the long history of Chinese art;

to the early Tang artists the spirit that impelled all things was a

terrible spirit, to be enclosed in forms of brutal energy, whilst to the

later and more sophisticated artists of the Song period that same cosmic

spirit was tender and lyrical.

Throughout its history, then, Chinese art conceives nature as animated

by an immanent force, and the object of the artists is to put themselves

in communion with this force, and then to convey its quality to the

spectator. Such an aim in Western art would lead to all kinds of dubious

romanticism and mysticism, but as if by a miracle the Chinese artist is

always saved from such troughs of sentimentality. This may be partly due

to the highly philosophical nature of the Chinese religions, though

artists are not necessarily given to the intellectual discipline which

saves the philosopher from sentimentality. But the Chinese artist is

given to the technical discipline which I have already described, and in

that discipline we must seek an explanation of the integrity and probity

of Chinese art even at its most cosmical. If a Chinese artist departed

from the intellectual dignity of his tradition, his handwriting would

betray him.

In its long history Chinese art was submitted to various vicissitudes.

Barbarians invaded the country from the north and west, and introduced

for a time an element of their geometrical style. But the most

distinctive variations are due to religious influences, to Buddhism and

Confucianism. No doubt, as always, these religions gave a tremendous

impetus to artistic activities of all kinds. But they also did a lot of

harm - Buddhism by its insistence on a dogmatic symbolism, always a

bad element in art; and Confucianism by its doctrine of ancestor

worship, which was interpreted in art as crude traditionalism, requiring

the strict imitation of ancestral art. But in spite of these

limitations, perhaps in some sense because of them, Chinese art

maintains its vitality, reaching its highest development in the Song

period, a period which corresponds roughly in time, and even more

strikingly in mannerism, with the early Gothic period in Europe.

|

艺术的真谛

[英] 赫伯特.里德 著 王柯平 译

42.中国艺术

中国艺术史要比埃及艺术史更富有连贯性、持续性和民族性。中国艺术大约从公元前13世纪开始,历尽沧桑,一直延续到现在。世界上没有任何一个国家能像中国那样,享有如此丰硕的艺术财富;从全面考虑,也没有任何一个国家能够与中国艺术的卓越成就相媲美。然而,中国艺术也有其局限性;从我们将要分析的原因看,中国艺术缺乏雄浑宏伟的作品。故而,中国的建筑比不上希腊或哥特式建筑。但在绘画与雕塑等其他艺术方面,中国艺术曾几度取得了一种完善无缺的形式美。

对于一般西方人来讲,尽管现代通讯和现代传递信息的方式(特别是照相机和电影院)为他们了解东方文明的外部特征提供了方便,但东方仍然是一个充满神秘色彩的地方,其内在的精神总显得奇异遥远,深奥莫测。每当我们触及东方文明中的精神因素时——如佛教与道教哲学——我们总是扮演一种同情和被动的旁观者角色,对那种难以理解的东方思维方式和生活方式可望而不可及。然而,当我们涉及物质的和客观的艺术品时——如雕像、绘画、陶器和纺织品——我们就不再那么谦恭自卑、不置可否了。我们认为,艺术是一种国际语言,可直接诉诸感官,从而使我们能够像欣赏自己的文明那样尽情地欣赏东方艺术。有关艺术普遍性的大量推测,虽然是模糊不清的,但却是鼓舞人心的。从17世纪迄今,东方艺术一直风行不衰,甚至给西方艺术家和手艺匠以创作的灵感。

然而,毋庸置疑,这些风尚始终是建立在对东方艺术的误解基础之上的,不是限于模仿东方艺术的一些表面特征,就是热中于选择一些劣等作品或风格加以临摹。现在,我们逐渐学会了如何依照东方的审美趣味来鉴赏东方的艺术品。在我们的博物馆里,那些曾使我们的先辈赞叹不已的精美而纯真的古董,正默默无闻地被堆放在隐蔽的地方,或埋藏在地窖里,目前人们正谋求展出真正的东方艺术品。这样,古代东方艺术的奥秘将被逐渐解开。有人认为,要想充分欣赏东方艺术品,就得诉诸新的眼光和新的世界观。因为,所有东方艺术家从来不是从我们的审美观点出发去观察世界的。

当我们的观点接近于东方艺术家的观点时,我们方可利用以下两种方法来欣赏他们的艺术。首先是难度最大的技巧方法。当然,欧洲绘画有着自己的技法,尽管缺乏中国绘画技法那种历史的连贯性,但也是一种难以掌握的法则。欧洲绘画技法涉及色彩理论、调色、上底色与笔触的不同效果等方面的知识,即一种有关现实事物在艺术中的复杂组合的知识。相比之下,中国绘画技法非常简单:它只要求具备使用一管毛笔和一种颜色的知识——但是,那管毛笔非常美妙,那种颜色如此精微,只有经过多年艰苦的练习才能达到运用自如的程度。众所周知,中国人通常用毛笔写字,他们对于毛笔就像我们对于钢笔和铅笔一样了如指掌。要知道中国绘画是中国书法的延伸。对于中国人来讲,美的全部特质存在于一个书写优美的字形里。一个人如果书法好,他的绘画也不会差。所有中国古代绘画都是强调线条的,这些构成绘画基本形式的线条,就像书法线条—样,能够唤起人们的判断、欣赏和愉悦之感。

故而,在西方,当我们以一个人的笔迹来判断其性格时,中国人则在大量科学和实践的基础上,以画家对线条的加工提炼程度来评判该艺术家的素质,因为线条往往具有无限的表现力。要了解—般绘画艺术是颇为容易的。但要了解中国绘画艺术,我们必须首先从中国其他艺术(如雕塑、陶器、青铜器和漆器等艺术)着手,从这些艺术中我们将会发现相似的技巧特征——即那种反映画家个性的无比精微的特征。譬如,在陶器艺术里,这种特征可以从陶器的轮廓上看出,也可以从其轮廓与其厚度和体积的关系中找到。当陶上经过陶工的双手黏接在旋转的轮子上时,便以微妙的方式表达了陶工的感觉,就像用蘸上墨汁的毛笔表现画家的感觉一样。在每一幅中国艺术作品中,都有艺术家本人的签名——这种签名并非是一种庸俗的自我意识的胡涂乱抹,而是古雅悠久的历史传统的产物。

关于欣赏中国艺术的技巧方法就谈到这里。下面介绍另—种方法,即形而上学的方法。中国艺术之所以令人难以理解和欣赏,是因为先前所述的那种完全个性化的技法同极端抽象和非个性化的内容结合在一起了。据说,中国艺术家试图在他的作品中表现出宇宙的和谐,有些关于宇宙的用语对描述中国艺术家的创作目的是十分必要的。无论怎么讲,这种目的与西方艺术那种再现自然表象细节的一般目的毫无共同之处。当然,中国画家也有描绘再现自然现象的作品:中国画家以山水画著名,但作品本身则是仔细观察自然现象的产物。这些山水画从来不只是某一特定的山水,而是在个别中包含着一般——

一种崇高感

来自情景交融的景色,

落日的余晖,

无边的海洋,流动的空气,

蔚蓝的天空,一并记入人的心灵,

一动,一跳,激发起

一切思想者,全部思想物

从万物中横穿而过。

在西方文化的全部领域中,再也找不出比华兹华斯[W . Wordsworth(1770—1850),英国浪漫主义诗人。——译者注]的这几行诗更合适的词句来表达东方艺术的精神了。自然,这种艺术精神在漫长的中国艺术史中经历了许多变化。对于初唐的艺术家来说,推动万物的精神是一种可怕的精神,它包含在冷酷无情的形式之中,但在晚唐和宋朝更为成熟的艺术家看来,这同一种宇宙精神却是温情脉脉的了。

有史以来,中国艺术便是凭借一种内在的力量来表现有生命的自然,艺术家的目的在于使自己同这种力量融会贯通,然后再将其特征传达给观众。这种目的可能会把西方艺术导向各式各样的、令人半信半疑的浪漫主义和神秘主义艺术。然而,中国艺术家总是奇迹般的从这种伤感主义的困扰中解脱出来。在一定程度上,这应归功于具有高深哲理特质的中国宗教。尽管艺术家不一定要像哲学家那样遵守一条不受感情摆布的理性原则,但却要遵守一条如上所述的技巧原则。从这一原则出发,我们一定会找到关于浩大无际的中国艺术的完整而笃实的理解。假如一位中国艺术家背离了其传统的理性风格,从他的书法中就会见出端倪。

在其悠久的历史长河中,中国艺术饱经风雨,历尽沧桑。从北部和西部侵入这个国家的野蛮人,在一个时期引进了他们的几何艺术因素。但佛教和儒教的影响仍然是导致中国艺术明显变化的主要原因。毋庸置疑,这些宗教长期以来大大地刺激了各种艺术活动,但也造成很大的副作用——对于佛教这一教条式象征主义宗教的执著,常常是有损艺术的一个不良因素;儒教对祖先顶礼膜拜的教义,要求艺术家严格模仿祖传艺术,这在艺术中被界定为原始传统主义。尽管有上述局限性因素,但在某种意义上,也许正是由于这些因素,中国艺术才得以保持其生命力,并在宋朝时达到了顶峰。宋朝艺术在时间上,特别是在表现手法上与欧洲的早期哥特艺术大体相近。 |

|

|

|

|